Preferred Citation: Babb, Lawrence A. Absent Lord: Ascetics and Kings in a Jain Ritual Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft8v19p2qd/

| Absent LordAscetics and Kings in a Jain Ritual CultureLawrence A. BabbUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1996 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: Babb, Lawrence A. Absent Lord: Ascetics and Kings in a Jain Ritual Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft8v19p2qd/

Acknowledgments

The research on which this book is based took place at two separate times and places. I spent the summer of 1986 in Ahmedabad doing a preliminary study of Svetambar Jain ritual; I was in Jaipur from August 1990 to May 1991 engaged in a more comprehensive study of Jain life. The Ahmedabad work was supported by a National Endowment for the Humanities summer stipend. My work in Jaipur was supported by a Fulbright senior research fellowship.

I would like to thank Professors D. Malvania and N. Shah of the L. D. Institute of Indology for their assistance and hospitality during my stay in Ahmedabad. I also owe special thanks to Dr. S. S. Jhaveri of Ahmedabad for his wise counsel and gracious efforts to further my understanding of the Jain tradition. I thank colleagues at the University of Rajasthan, especially in the Department of History and Indian Culture, for their generous assistance during my stay in Jaipur. I gained more than I can easily say from the intellectual stimulation of conversations with these colleagues, especially Dr. Mukund Lath. I also thank Arvind Agrawal for his generous assistance in getting me settled and started in Jaipur. I am indebted to too many members of Jaipur's Jain community to mention all of them here. I owe special thanks, however, to Mr. Rajendra Srimal and Mr. Milap Chand Jain for their extremely generous reponses to my inquiries. I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to my good friend and colleague Surendra Bothara for his companionship and guidance. There were

many other good friends who made Jaipur into a second home for Nancy and me. To Daya and Francine Krishna, Mukund and Neerja Lath, Fateh and Indu Singh, Rashmi Patni, and Arun and Vijay Karki we both send our most affectionate thanks.

In response to both oral and written versions of this manuscript (or parts thereof) many colleagues have given me helpful criticism and comment. I am especially indebted to Phyllis Granoff, James Laidlaw, and John Cort. John Cort, in particular, has been an unfailing source of encouragement, an absolutely reliable critic, and a true and good mentor in all things Jain. My thanks indeed. But to all these thanks I must add that any errors of fact and interpretation are mine alone.

My wife Nancy has shared my life in India through good times and bad and has helped me in my work in ways too numerous to mention. To say that I am grateful hardly expresses what I feel, but grateful I am.

Some portions of this book consist of revised and recast material drawn from earlier articles of mine. I am grateful to History of Religions and the University of Chicago Press for permission to use materials from "The Great Choice: Worldly Values in a Jain Ritual Culture" (Babb 1994, © 1994 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved), and also to the editors of Journal of Anthropological Research and The Journal of Asian Studies for permission to use materials, respectively, from "Giving and Giving Up: The Eightfold Worship among Svetambar Murtipujak Jains" (1988) and "Monks and Miracles: Religious Symbols and Images of Origin among Osval Jains" (1993).

A Note On Transliteration

I have employed standard conventions for the romanization of words from Indian languages. Words from Indian languages have been pluralized by adding an unitalicized "s." I have used diacritics on personal names and many place names (although I have used conventional spellings for such familiar place names as Ahmedabad and Delhi). The Hindi retroflex flap and the Sanskrit vocalic "r " are both reproduced as "r ." The soft-palatal nasal in words like sangh is represented by an unmarked "n ." Many of the Indic words reproduced in this book have both Hindi and Sanskrit forms, with the Hindi form dropping the final "a " (dana thus becoming dan ). In keeping with the vernacular milieu of the study, I have privileged the Hindi forms throughout most of the book (Mahavira therefore appearing as Mahavir). In some cases, however, I have bowed to conventions employed by secondary sources on which I rely heavily and have given the more familiar Sanskrit versions (for example, Saiva and Vaisnava). Occasionally, moreover, context or common practice has made it seem desirable to give the word in question in its Sanskrit form even though it has been given in its Hindi form elsewhere in the book. When this has been done, both forms are included in the glossary. Recurrent and important terms, but not all Indic terms, are included in the glossary; Hindi glosses given in the text are not given in the glossary.

Introduction

What does it mean to worship beings that one believes are completely indifferent to, and entirely beyond the reach of, any form of worship whatsoever? What are the implications of such a relationship with sacred beings for the religious life of a community? These turn out to be questions that can be investigated and answered, for a very close approximation of such a state of affairs can be found in the South Asian religious traditions known collectively in English as Jainism. This book is an exploration of one of Jainism's several branches from the standpoint of the interactions—real, putative, or lacking altogether—between human beings and the sacred entities with which they attempt to build ritual relationships.

The book deals with these issues at two levels. Most of the book is a consideration of a specific Jain tradition on its own terms. As readers will come to see, to worship entities such as those worshiped by the Jains is to possess a very specific understanding of the nature and meaning of ritual. My goal is to characterize this understanding and to trace its implications for other areas of Jain religious life. My readers will, I hope, come to see that divine "absence" can be as rich as divine "presence" in its possibilities for informing a religious response to the cosmos. At the same time, however, Jain traditions exist as part of a wider South Asian religious universe. At the end of the book I place Jain traditions in a broader context by showing how they relate to ritual patterns found in other Indic traditions.

The Jains

Jainism is Buddhism's lesser-known cousin; although their belief systems are in some ways radically different, they are together the only surviving examples of India's ancient non-Vedic religious traditions. Jainism is above all, and justly, celebrated for its systematic practice of nonviolence (ahimsa ) and for the rigor of the asceticism it promotes. Jainism is Sometimes said to have been founded by Mahavira in the sixth century B.C.E . In reality, however, Jain traditions are much older than this, dating back in all probability to the teachings of Parsvanath, who lived in the ninth century B.C.E . Unlike Buddhism, Jainism never (until quite recently) spread beyond India; but also unlike Buddhism, it did not die out in India, and it continues to be an important element in India's contemporary religious life. Although the Jains are relatively few (currently they probably number around four million), many among them enjoy positions of great power and influence in modern Indian society. In northern India the Jains are concentrated mainly in Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan; farther south they are found mainly in Maharashtra and Karnataka. Jains, however, live everywhere in India, and significant numbers of Jains also live in Europe and North America.

Jains have a strong and conspicuous religious identity in India. Their monks and nuns are frequently seen in India's urban centers, and are readily identifiable as Jain mendicants. The rigor of both monastic and lay Jain ascetic praxis is widely known and admired. This asceticism is manifested in many ways, but emblematic of its uncompromising se-verity—in the public eye and in reality—is the fact that death by self-starvation (sallekhana ) is enshrined as one of Jainism's highest ideals. Jains are also widely known to place great emphasis on the principle of nonviolence. For non-Jain observers this is dramatized by the brooms carried by Jain mendicants for the purpose of removing small forms of life before sitting or lying down, and by the practice of some Jain mendicants of donning masks to prevent the wearer's breath from harming microscopic forms of life in the atmosphere. The commitment to non-violence is also publicly manifested in the generous support lay Jains give to animal welfare organizations and to organizations promoting vegetarianism. Few visitors to Delhi fail to notice the Jain Birds' Hospital, conspicuously located at Chandi Chawk in one of the busiest concourses of the city.

Lay Jains also bear a stereotypical social identity as wealthy traders.

However, this element of Jain identity requires qualification. It is not true that all Jains are traders; Jains are found in diverse occupations, and in fact in the south some Jains are farmers. Nor is it the case that all Jains are wealthy, although many undeniably are. Nonetheless, for centuries the Jains have been strongly identified with trade, and in the north Indian region—which is the cultural locale of this study—they are predominantly a merchant community. It should also be said that business in general tends to be the most admired occupation among the Jains of this region. Jains are renowned for the munificence of the monetary donations they provide for the upkeep of their temples and other religious institutions. Their temples are famous for their lavish-ness and also for their cleanliness.

In North India the general social category to which Jains are assigned by others carries the label Baniya , which is an all-purpose term for traders and moneylenders. It is not a term that applies specifically to Jains, for various Hindu groups belong to this category as well. Most groups belonging to the Baniya category—Jains or not—share a generally similar lifestyle and social persona. Probably the most important of their shared characteristics is a strict vegetarianism, which in fact is a strong social marker of Baniya status. The term Baniya is also a word with definite negative connotations of miserliness and shady dealing. To note this is, of course, not to endorse such a judgment. Most non-Jains refer to Jains more or less automatically as Baniyas, but because of the unfortunate associations of the term, many Jains (and non-Jain Baniyas as well) do not use this term in self-reference (on these points, see Ellis 1991 and Laidlaw 1995:Ch. 5). The preferred term is Mahajan , which literally means "great person." This word lacks the negative connotations of Baniya, and is generally seen as referring to the category of merchants and traders, both Jain and non-Jain.

To what degree do the Jains see themselves as an actual community of co-religionists? The question of Jain identity in relation to other religious identities is a complicated matter. For present purposes let it suffice to say that this remains an ambiguous issue and that Jains are continuing to negotiate their identities—religious and social—to the present day. A heightening of Jain self-identification as a discrete religious community seems to be a relatively recent development. As Paul Dundas points out (1992: 3-6), Jains often reported themselves as "Hindu" in the early British censuses, and even today Jains see this question in more than one way. Some Jains accept the label Hindu , understanding the term in its most inclusive sense, while others are more

adamant in the claim to a completely separate Jain identity. Many Jains worship at Hindu temples and participate in Hindu festivals. These issues are, of course, greatly complicated by the fact that the status of "Hinduism" as a unified religious tradition is itself doubtful and contested, and that "Hindu identity" is a historically recent phenomenon. The modern tendency is probably in the direction of a Jain identity separate from that of Hindus, but this transformation is far from complete and will probably never be completed. There appear to be, moreover, countervailing forces. For example, my own general observation is that, as religious politics has become increasingly important in India, large numbers of Jains have identified with the Hindu nationalist viewpoint with hardly a second thought.

Within the Jain community—if it is a community—there are many fissures and cleavages. The most important division is the sectarian divide (and rivalry) between the Svetambars and the Digambars. The term Svetambar means "white clad" in reference to the fact that mendicants of this branch of Jainism wear white garments. Digambar means "space clad," which is to say unclad, and the term refers to the fact that male mendicants of this branch wear nothing. These two great branches of Jainism possess different bodies of sacred writings and are also radically distinct socially. Even when they live in the same locality, their adherents are drawn from totally different castes. In Jaipur—one of the principal sources of material for this book—most Digambar Jains (sometimes collectively called Saravgis)[1] belong to either the Khandelval or the Agraval caste, with the former predominating. The Svetambars mostly belong to the Osval and Srimal castes, a point to which we shall return later.[2] These caste differences mean that there are few social fields, such as marriage, within which sustained and intimate interaction can take place. The only occasion in which I ever saw significant interaction between Digambar and Svetambar Jains was in connection with the pan-Jain festival (and Indian national holiday) of Mahavir Jayanti (Lord Mahavira's birthday). For all practical purposes, they exist in totally different worlds.

This book is mainly concerned with a subbranch of the Svetambar Jains. The Svetambar branch of Jainism is (as is the Digambar branch as well) divided into sects and subsects. The principal division is between those who worship images in temples and those who do not. Image-worshipers are known as Murtipujak (image-worshiping) or Mandirmargi (temple-going). The practice of image-worship is opposed by two reformist sects, the Sthanakvasis and the Terapanthis. I am con-

cerned here entirely with the image-worshiping group. The image-worshipers are further subdivided by caste and by affiliation with differing ascetic orders. These divisions will be discussed in greater detail later.

Jain Basics

Despite major sectarian differences there is enough common ground among Jain groups that one may legitimately speak of "Jainism," a Jain religious tradition in a general and inclusive sense. Who, in this sense, is a Jain? The answer is in part supplied by etymology. "Jain" means "a follower of a Jina." The term Jina , in turn, means "victor" or "conqueror," by which is meant one who has achieved complete victory over attachments and aversions. A Jain is someone who reveres and follows these personages and regards their teachings as authoritative. This is the sine qua non of all forms of Jainism.

The term Jina itself tells us something of great importance about Jainism. Jainism's emphasis on nonviolence might foster the impression that this is a tradition that emphasizes mere meekness or docility. Such an impression, however, would be quite mistaken. Martial values, albeit in transmuted form, are crucial to Jainism's message and to its understanding of itself. The Jina is a conqueror. As we shall see later, he is also one who might have been—had he so chosen to be—a worldly king and a conqueror of the world. But instead the Jina becomes a spiritual king and transposes the venue of war from the outer field of battle to an inner one. As I shall show, the metaphor of transmuted martial valor is basic to the tradition's outlook and integration.

The Jinas are also called Tirthankaras (in Hindi, Tirthankars, which form I use from this point on). This term means "one who establishes a tirth ." The word tirth has two meanings. Its primary meaning is "ford" or "crossing place." In this sense, the Tirthankar is one who establishes a ford across what is often called (by Hindus as well as Jains) "the ocean of existence." The term also refers to the community, established by the Tirthankar, of ascetics and laity who put his teachings into practice; such a community is itself a kind of crossing place to liberation. A Tirthankar is a human being. He is, however, an extraordinary human being who has conquered the attachments and aversions that stand in the way of liberation from worldly bondage. By means of his own efforts, and entirely without the benefit of being taught by others, he has achieved that state of omniscience in which all things are known to him—past, present, and future. But, before final

attainment of his own liberation, the Tirthankar imparts his self-gained liberating knowledge to others so that they might become victors too. Thus, he establishes a crossing place for other beings.

By either name—Jina or Tirthankar—these great personages are the core figures of all forms of Jainism. Not only are their teachings central to Jainism but they themselves are also Jainism's principal objects of veneration, and this is true whether or not they are actually represented by images in temples. However—and this is a fact crucial to this study—they are not believed actually to interact with their worshipers. This is because they are no longer present in our part of the cosmos. They came, achieved omniscience, imparted their teachings, and then they departed. And when they departed they became completely liberated beings. In this condition they have withdrawn entirely from any interaction whatsoever with the world of action and attachment. They dwell forever at the apex of the cosmos in a condition of omniscient and totally isolated bliss. Their former presence, however, has left strong traces in the world. They left their teachings behind, and also a social order (called the caturvidh sangh ) consisting of four great categories: sadhus (monks), sadhvis (nuns), sravaks (laymen), and sravikas (laywomen). The monks and nuns are those who most directly exemplify the Tirthankars' teachings in their manner of life. The term sravak and its feminine counterpart, sravika , mean "listener." The sravaks and sravikas , that is, are those who hear the Tirthankars' teachings. The Tirthankars also left behind them a kind of metaphysical echo of the welfare (kalyan ) generated by their presence that continues to reverberate in the cosmos and that can be mobilized by rituals and in other ways at the present time (Cort 1989: 421-22).

An infinity of Tirthankars has already come and gone in the universe, and indeed there are Tirthankars teaching at the present time in regions of the cosmos other than ours.[3] In our region, twenty-four Tirthankars have appeared over the course of the current cosmic period. The last of these was Lord Mahavira (hereafter I shall use the Hindi form, Mahavir), who lived, taught, and achieved liberation some 2,500 years ago. In our sector of the world there will be no more Tirthankars until after the next cosmic time-cycle has begun. The twenty-four Tirthankars who have come and gone in our region are the principal beings represented by images and worshiped by image-worshiping Jains. It is true that Jains also worship deities who are not Tirthankars. But as we shall see, the worship of such beings—if, indeed, it is worship

at all—is seen as entirely subordinate to the worship of the Tirthankars themselves.

It should be clearly understood that, from the standpoint of the Jain tradition itself, the Tirthankars were in no sense the creators of Jainism. From an outsider's point of view, Mahavir can be seen as someone whose teachings drew upon traditions existing at the time, and who probably elaborated on those teachings in his own distinctive way.[4] From the Jain point of view, however, Mahavir created nothing, for the teachings of Jainism have existed from beginningless time and will never cease to exist.[5] It would be a major mistake, moreover, to think of Jain teachings as resembling speculative philosophy in any way. From the tradition's standpoint, Jain teachings do not stand or fall on rational arguments; rather, the sole and sufficient guarantee of their validity is the Tirthankars' omniscience. These teachings are not only regarded as unconditionally true; they are also enunciated for one specific purpose and for no other reason. That purpose is the attainment of liberation from the world's bondage.

In common with other South Asian religious traditions, Jainism teaches that the self or soul is ensnared in repeating cycles of death and rebirth. Liberation is escape from this cycle. The Jains believe that the cycle is without beginning or end; neither the cosmos nor the souls that inhabit it were ever created, nor will they ever cease to be. Each soul has therefore already been wandering from birth to death to birth again from beginningless time, and unless liberation is attained, the soul will continue so to wander for all of infinite time to come. Thus, the stakes are high indeed. As a Jain friend once put it to me, "Bondage is anadi (beginingless) but not necessarily anant (endless)." But whether one leaves the cycle or not depends entirely on one's own efforts, and what is required is not easy.

Central to the Jain view of the predicament of the soul is the distinctive Jain theory of karma . The concept of karma is basic to all South Asian religious systems, but the Jains have given it a unique twist. In general, the term refers to actions and their results. We act and experience the results of our acts; that is, we consume (and must consume) the fruit (phal ) of our actions (karmas ). Because actions inevitably have consequences, our actions and their results constitute a self-replicating concatenation that pulls the soul through the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. The Jains share this general view with other South Asian systems, but they also—as others do not—maintain that karma

is an actual physical matter that is attracted to the soul by an individual's actions and adheres to the soul because of the individual's desires and aversions (rag and dves ). This view is one of the most distinctive features of the Jain belief system.

The accumulations of karma on the soul are responsible for the soul's bondage. This is because they cover the soul and occlude its true nature, which is omniscient bliss. The keys to liberation, therefore, are two. First, one must avoid the accumulation of further karma . Violent actions are particularly potent sources of karmic accumulation, and this is the foundation of the tradition's extraordinary emphasis on non-violence. Second, one must eliminate the karma already adhering to the soul. The fact that karma is viewed as an actual physical substance means that the most radical measure will be required for its removal. This radical measure is ascetic practice of great severity. The tradition's recurrent image is that of asceticism as a kind of fire that burns away the soul's karmic imprisonment; hence, ascetic values are central to the tradition's highest aspirations.

The Jains visualize the attainment of liberation (moks, nirvan ) as a process that occurs in stages (called gunasthan s), although it can occur very quickly in the case of certain extraordinary individuals. Liberation is preceded by the attainment of omniscience (kevaljnan ), which is an innate quality of the soul that becomes manifest when certain occluding karma s are removed. After a period of time (which may be quite lengthy) during which certain remaining karmic matter is removed, the body ceases to function; then, after the last karmic vestiges are shed, the soul rises to the abode of the liberated (siddh sila ) at the very top of the cosmos. There it abides in omniscient bliss for all of infinite time. The liberated beings are known as siddh s, and are infinite in number. Among them are the liberated souls of the Tirthankars and also the liberated souls of others who did not, as did the Tirthankars, find the path to liberation on their own and teach it to others.

The Problem

I have provided the foregoing brief sketch of Jain doctrine in order to introduce what seems to me to be the central analytical problem presented by Jainism to the student of religious culture. At Jainism's highest levels, by which I mean Jainism as embodied in its most important sacred writings, we are dealing with a soteriology, not a way of life. The question is, how can such a soteriology be woven into a way of

life? This question is given special force and interest because of this tradition's extreme emphasis on nonviolence and asceticism.

It is clear that faithful adherence to Jainism's highest ethic, which is nonviolence, necessarily means a radical attenuation of interactions with the world, and in this sense nonviolence and asceticism can be seen as two sides of the same coin.[6] In the last analysis, all actions—eating, movement, whatever—inevitably result in harm to other beings. The behavior of men and women who are not Jains creates the most damage. The meat eaters of this world, the fighters of wars, the butchers, the choppers of trees, and so on leave a vast trail of carnage wherever they go. Observant lay Jains create havoc, but less havoc. Restrictions apply to them—restrictions of diet, occupation, and other kinds too. As a result, they, at least, confine the harm they do to the smaller and less highly organized forms of life, as will be seen in Chapter One. Jain ascetics create the least harm of all. Theirs is a manner of life maximally governed and restricted—or, to put it in the obverse, minimally free. The many rules and regulations that govern their lives ensure that minimal harm is done to other beings, even the most microscopic.

Given all this, it is clear that from the standpoint of Jain teachings the more restrictions to which conduct is subject the better. Moreover, it is also clear that to the degree that such restrictions are applied, the individual's sphere of activity becomes limited and his or her aperture of interaction with the world and other beings becomes closed. At the ideal limit of the application of this principle we find a complete cessation of all activity and of interactions with matter and other beings. This is in fact what liberation is. Liberated beings are entirely devoid of attachments and aversions (that is, they are what Jains call vitrag ) and exist in a state of total isolation. In their turn, those who seek liberation—that is, those who are followers of the Jinas—should try to approximate this state of affairs as best they can, given the many existing limitations of their power to do so.

What place can there be for such a radically world-rejecting vision of the world in the lives of ordinary men and women? This is the crucial question in the study of Jainism as a cultural entity as opposed to a strategy for attaining liberation. For any radically world-rejecting religious tradition to succeed in the midst of the world's endeavors—that is, for it to exist as a reproducible social institution—there must be points of connection between the central values it affirms and the ends pursued by adherents who make their way in the world. Ascetics require the support and protection of those who are not ascetics, and this

means that nonascetics must somehow be brought into the ambit of a wider tradition that encompasses the religious interests of those who do and those who do not renounce the world. In the particular case of Jainism, the tradition's highest values define a way of life suitable only for a mendicant elite—the monks and nuns—but at the same time this elite cannot exist without the support of lay communities. One of the most striking features of Jainism, as we shall see, is that the monastic elite is utterly dependent on the laity. Therefore, a Jain tradition in the fullest sense, as opposed to a mere soteriology, cannot be for mendicants alone; it must bring ascetics and their followers into a system of belief and practice that serves the religious interests of both. How can such a religious system "work" when asceticism is so central a value?

This book addresses this general problem.[7] It does so, however, within a special frame of reference. Our attention will be directed mainly to ritual, and especially to rituals of worship.[8] The advantage of this approach is that rites of worship provide a lens through which the very large question of worldly and otherworldly values in Jainism can be brought into a precise and manageable focus. It should not be imagined, moreover, that ritual is a peripheral aspect of the Jain traditions with which we shall be concerned. Rites of worship define one of the principal venues within which lay Jains of the image-worshiping groups actually come into contact with their religion. This being so, a focus on such ritual is one good way (certainly not the only way) to understand Jainism as a living tradition.

At the level of ritual the Svetambar Murtipujak tradition's commitment to otherworldly values is manifested in the form of a particular ritual pattern, namely, the veneration of ascetics. Above all else, as we shall learn, Jains worship ascetics. But to be committed to the worship of ascetics is to confront an inherent contradiction. The greater the ascetic's asceticism, the more worthy of worship he or she becomes. But the greater the asceticism, the less accessible is he or she to interaction with worshipers. The logic of the situation drives ineluctably toward the paradox that the most worshipable of beings is inaccessible to worship by, or to any other form of interaction with, beings remaining in the world. This is the problem of reconciling worldly and otherworldly values in Jainism as it is manifested in the ritual sphere.

As noted already, the Tirthankars are the supreme embodiment of Jain ideals. Because of this, they are the principal objects of worship in Jainism. But precisely because they exemplify the tradition's highest values-ascetic values—in the highest degree, they are, in the world of

ritual logic, inaccessible to worship. Hence, the question with which this book began: What does it mean to worship entities of this sort? How, to expand on the question, does one deal with them in ritual? What can one gain by doing so? And what implications does worshiping such beings have for the worshiper's relations with the world? These are the questions addressed in the chapters to follow.

As we shall see, this approach is not as narrow as it might appear to be at first. It will lead us to the most general issues concerning the religious and also the social identities of lay Jains. Moreover, it will propel us beyond the boundaries of Jainism to questions concerning Jainism's place in the Indic religious world.

Ritual Culture and Ritual Roles

In this book I frequently use the expression "ritual culture." In doing so I have more in mind than the scarcely controversial notion that rituals are manifestations of culture. Rather, I want to suggest that rituals actually occur within a cultural mini-milieu, a cultural domain associated specifically with rituals. I want to suggest further that this domain can be treated as a partly autonomous context of investigation. Ritual culture in the sense I have in mind is not just a bundle of recipes for the performance of rites of worship. Nor is it merely an ideology that justifies or rationalizes ritual activities. Rather, it is an internally coherent body of skills, kinetic habits (such as patterned physical gestures expressive of deference), conventions, expectations, beliefs, procedures, and sanctioned interpretations of the meaning of ritual acts. It is, one might say, an entire symbolic and behavioral medium within which ritual acts are invested with cognitive, affective, and moral "sense."

Ritual culture, thus defined, is carried—in part—as a component of the general cultural repertoire of those who perform rituals. It also forms a sort of peninsula of what might be called "religious culture," although for those whose contact with a religious system is primarily in the sphere of ritual, ritual culture may indeed be the continent and not the appendage. Its boundaries are thus always a bit hazy. It is never a closed system. But it can nevertheless be seen as a partly independent reality—independent in the same sense, let us say, that "political culture" can be treated as a cultural subsystem. In traditions that have them, ritual specialists can act as special repositories and transmitters of ritual culture. To some extent, laymen who have acquired special rit-

ual expertise play this role in Svetambar Jainism, as do some monks, although the latter are not seen as ritual specialists. Ritual culture is also deposited in, and transmitted by, certain kinds of writings. These may be writings that instruct people about how to perform rituals, texts sung or recited in rituals, or texts of other kinds; the important thing is that they are part of the immediate surround in which rituals are performed. Writings of this sort, mostly authored by monks or nuns, are a very important aspect of the ritual culture of temple-going Svetambar Jains. Ritual culture is also embodied in, and transmitted by, the ongoing talk about ritual—instruction, rationalization, interpretation, whatever—that takes place in a given community of co-ritualists. But although ritual culture is carried in a variety of media—writing, talk, even emotional and motor habit—it becomes visible mainly in actual ritual performances.

The allusion to "performance" is not accidental and brings us to an important point. The rituals discussed in this book are excellent examples of what Milton Singer has called "cultural performances"—performances that encapsulate culture in such a way that it can be exhibited to the performers themselves and also to outside observers (1972: 71). In fact, the dramaturgic comparison can be pressed even further than this. As readers will see, the rituals discussed in this book bear a close resemblance to actual theatrical performances. But they are not just the same as theatrical performances, and the difference is important.

As Richard Schechner has pointed out (1988, esp. Ch. 4), theater and ritual belong on the same general continuum of "performance," and whether a given performance is theater—in the strict sense—or ritual depends mainly on its context and ostensible function. The real essence of what we normally consider theater is its function as entertainment. Ritual, on the other hand, is supposed to be efficacious, by which we mean that it is supposed to bring about transformations of some kind or another. Associated with this difference, in turn, are others, and perhaps the most important of these has to do with the relationship between performers and audience. Where entertainment prevails—that is, in theater—the audience and performers are separated. To be a member of the audience in theater is to be "out of the action," a spectator and a potential critic. To the degree that a performance belongs to the ritual category, on the other hand, audience and performers are one and the same.

These insights provide us with a useful way to view Jain ritual. Jain rites of worship are certainly theater-like performances, but at the same time they are not quite theater in the usual sense of the English word. As we shall see, the question of what actually constitutes the "efficacy" of ritual is one of the central problematics of Jain religious life. Nonetheless, in Schechner's terms, efficacy, not entertainment, is what Jain rites are basically about, although this certainly does not preclude individuals from taking pleasure in the spectacle of their own performances or of those of others. Moreover, this is theater in which the players are largely their own audience. It is true that groups of participants sometimes assume a spectator-like stance in some Jain rituals, but the general principle still holds that the audience is part of the action. The principle finds its logical limiting case in one of the most important Jain rites of worship—the eightfold worship (astprakari puja ) —in which the performer and audience can be said to be a single person.

Where there is theater, of course, there are performers playing in roles, and this brings us back to the matter of ritual culture. As is true of the larger stage of social life, the roles played by actors in the theater-like performances of ritual are manifested in interactions with the occupants of other roles. In this sense, rituals can be understood not only as performances but as minute and ephemeral social systems. Ritual culture is the environment—cognitive, affective, and even motor-habitual-that supplies much of the content of such role-governed interaction and also the wider frame of reference within which that content is meaningful to ritual performers.[9] Ritual roles and ritual culture are thus mutually dependent. Ritual roles may be said to express ritual culture; ritual culture in turn shapes ritual roles.

These ideas are unremarkable, but to them I add what may strike some readers as an unusual twist. To assert that human participants in rituals play roles is uncontroversial. They walk on the ritual stage as supplicants, offerers, experts, interested onlookers, or whatever—the list is potentially long. Here, however, I shall interpret the entities who are objects of worship as also "playing" a role. I shall say further that such entities are, from an analytical standpoint, role players whether or not they are living persons.

Moreover, I shall say this role—that of object of worship—is one of the two basic constituent features of any rite of worship. That is, in the simplest instance a rite of worship necessarily encompasses two elementary roles. There is, first, the role (which may be differentiated into sub-

roles) of those who worship; these are the human performers of ritual acts. They initiate ritual performances, set the stage, make offerings and direct other kinds of honorific attentions to the object or objects of worship, and bring matters to a conclusion. They typically expect results (Schechner's efficacy) to flow from what they have done. They may play differently scripted parts in the performance, but in the widest frame of reference they may all be considered "worshipers." Second is the role occupied by certain very special others, the objects of worship. From the standpoint of our model, worshipers and objects of worship may be considered ritual/social "alters" of each other.

The possible objection that, in rites of worship, the worshiper's alter—the object of worship—is not "real" is irrelevant to this formulation. In the first place, the role of object of worship is often occupied by living human persons. This is frequently true in Jainism as well as in other South Asian religious traditions. But even more important, whether this role is occupied by a living (and thus kinetically and verbally interacting) person or an (apparently) lifeless image, or even a completely disembodied or disengaged being, the crucial thing for the worshiper is how he or she thinks the ritual other reacts (or does not react) to ritual acts, and this is always imaginary from the worshiper's perspective. This is true whether or not the alter is a living person. It is enough that the act of worship takes place; if it does, then from the standpoint of the worshiper an interaction has occurred, and the ritual alter may be said to be as real as the interaction itself is felt to be real.

To push matters slightly further, I shall also say that the roles of worshiper and object of worship must be seen as reflexes of each other. This is because both roles are shaped by their mutual interaction; they are the "others" of each other, and thus each is—in part at least—a product of the other. It is, moreover, precisely in this mutually creative relationship that the behavioral characteristics of ritual roles and the content of ritual culture most dramatically intersect. What worshiper and worshiped actually are to each other depends on ambient habits of thought, emotion, evaluation, as well as on prevailing assumptions about the nature of the world and the nature of persons or beings in the world. That is, it depends on the general cultural background of ritualists and, more immediately, on their ritual culture. In turn, this ambient atmosphere, having been given embodiment in the form of ritual acts (whether or not the occupants of all roles act in the kinetic sense) of a

particular kind, is thereby supported and regenerated. For example, a conception of the object of worship as lofty and remote fits well with a worshiper's ritually enacted attitude of humility. This relationship, in turn, is deeply resonant with a more general notion of the worshiper as slavelike and dependent on an all-powerful other, and these notions, in turn, can open out into a complex theology of divine majesty and power. All this can and does come together in crystallized form in ritual interactions. By contrast—and as one sees especially in some subtraditions of the worship of the Hindu deity Krsna —a portrayal of the object of worship as childlike meshes with a worshiper's role defined as nurturant and maternal. This, in turn, supports, and is supported by, a very different vision of the world and the worshiper's place in it: a theology of reciprocated parental and filial devotion. All this, too, can be distilled in ritualized interactions between devotees and the objects of worship.

But what if, as in Jainism, the principal object of worship is absent ? What implications would this have for the worshiper's identity and for the cultural surround of these ritual roles? These issues provide the basic point of departure of this book. What kind of a ritual system results, we wish to know, when a commitment to asceticism as a value is so powerful as to push objects of worship into a condition of transactional nonexistence?

There is one final point to be made about ritual roles. For human worshipers—the self-audiences of this particular kind of theater—playing such roles leaves deposits of feeling and conviction that can outlast the ritual situation, augmenting a worshiper's sense of identity on both the personal and social planes.[10] The ritual setting is extraordinary, a special time and place set apart from all mundane times and places. Given this extraordinary context, the object of worship is not only a social alter of the worshiper but an alter quite unlike any other—a hypersignificant other in a hypersignificant situation. When the worshiper enters a relationship with such a being, he or she is thrust into a defined role in relation to this being. Depending on how the ambient ritual culture characterizes the situation, this role can impart to the worshiper a sense of extramundane personal identity—as one who is powerful in some special way, or beloved of God, or redeemed, or on the road to liberation. Moreover, and as this book will show, it can also—and at the same time—impart a special kind of significance and energy to a worshiper's social identity, in the present case that of clan

and caste. In the materials to be presented here, ritual emerges not just as theater-like, but as a theater of soteriological and social identities.

The concepts of ritual culture and role constitute the basic frame of reference within which Jain materials are interpreted in this book. One important consequence of this approach is the manner in which materials are presented here. Religious traditions are often described and analyzed as "systems of belief." An account based on this idea typically describes religious ideas and values first, with ritual coming only later. The basic (though usually unstated) idea is that ritual is a kind of behavior that is somehow deductively related to beliefs. In this book, however, I take the opposite approach. Instead of treating ritual as a behavioral surface of beliefs, I treat the entire domain of ritual as an analytical shell within which matters of belief are (sometimes) best understood. In my view, this is far closer than the conventional approach to the tradition's experiential reality for most Jains. As a practical matter this means that in this study we begin with rituals instead of ending with them, and what we learn of beliefs we learn from rituals and the texts associated with rituals.

A second consequence of this approach is that this book stresses ritual roles and interactions, and indeed is organized around these concepts. In this sense the book might be understood as an attempt to push social concepts to the center of the analysis of religious symbolism. Who are the dramatis personae in ritual performances? Who is worshiped? Who does the worshiping? How do these roles interact in ritual settings, and what significance do these patterns have for the over-arching question of how Jainism (or one variety of Jainism) deals with the tensions between otherworldly values and the requirements of life in the physical and social worlds? These are the guiding questions taken up here.

In approaching these questions, moreover, we shall give special attention to the kinds of exchanges and transactions that are engaged in, or are not engaged in, by occupants of ritual roles. This connects the study with a tradition of social analysis that can be said to have begun with Marcel Mauss (1967; orig. 1924) and that more recently has—especially in the work of McKim Marriott (1976, 1990), Jonathan Parry (1986, 1994), Gloria Raheja (1988), and Thomas Trautmann (1981)—produced major advances in social scientific understanding of ritual gifting in South Asia. These new insights will play an important part in the book's final chapter in which Jain ritual patterns are compared with other South Asian ritual cultures.

Two Cities

My materials are drawn from two periods of field research. I spent the summer of 1986 in the Gujarati city of Ahmedabad. Here my work was quite narrowly focused on the structure of the principal Svetambar rite of temple worship (the eightfold worship or astprakari puja ).This initial investigation was followed by a stay of several months in Jaipur, the capital city of Rajasthan, in 1990-91 (see map of Gujarat and Rajasthan). This time my research was much more broadly based. Ahmedabad is a major Jain center and is dominated by the Svetambar sect; my work in this city was entirely with Svetambar Jains. Jaipur also has a large Jain population, but its composition is very different from Ahmedabad's. Most Jaipur Jains are Digambars, but there is also a relatively small but flourishing Svetambar community, mainly supported by the gemstone business.[11] In general, Jaipur's Svetambar community has been a business community, whereas the Digambars have been more prominent in service occupations. As in Ahmedabad, my work in Jaipur was focused mainly on the Svetambars, but I was also able to learn something about Digambar traditions during my stay in this city.

An important difference in my work in these two cities has to do with caste.[12] Caste was hardly relevant at all to my work in Ahmedabad, but it became a significant element in my investigations in Jaipur. Here the principal Svetambar castes are only two, the Osvals and the Srimals, who are more or less equal in status but with the Osvals the larger of the pair. In Jaipur the division between superior bisa and inferior dasa sections, so important to intracaste stratification among Osvals and Srimals elsewhere, seems to have fallen into desuetude, and intermarriage between Osvals and Srimals is not uncommon. My concern was primarily with the Osvals of Jaipur, and particularly with the relationship in this caste between Jainism and clan and caste identity.

The image-worshiping Svetambar communities in Ahmedabad and Jaipur are very similar in most ways. The principal difference is that in Ahmedabad (and in Gujarat generally) most temple-going Svetambar Jains are linked with a particular ascetic lineage—that is, a lineage of monks and nuns based on disciplic succession—called the Tapa Gacch, whereas in Jaipur the dominant ascetic lineage is the Khartar Gacch. This in itself is a highly significant fact about the two communities. The Tapa Gacch is currently in a flourishing state, with large numbers of monks and nuns. The Khartar Gacch is much smaller and

Gujarat and Rajasthan with selected locations

seems to be languishing at the present time. This means that the lay Svetambar Jains of Ahmedabad enjoy much more sustained contact with monks and nuns—especially monks—than do their co-religionists in Jaipur. Khartar Gacch nuns are almost always present in Jaipur, but monks visit only from time to time. This issue aside, however, the ritual practices of the two communities are very similar in most ways. Accordingly, my treatment of general ritual idioms—by which I mean

those associated with the worship of the Tirthankars—is based on materials drawn from observations in both cities.

At another level, however, there are certain special features of the Jaipur scene to which I shall give very close attention. Associated with the Khartar Gacch is a complex of ritual and belief—a "ritual subculture," as I call it—based on the veneration of certain deceased monks known as Dadagurus or Dadagurudevs. The cult of the Dadagurus is central to the ritual pursuit of worldly success among the Svetambar Jains of Jaipur, and it is also linked to the origin mythology of clans belonging to the Osval caste. This is where caste becomes relevant in the Jaipur context. An extended discussion of the cult of the Dadagurus will enable us to see how, in one Svetambar community, the tension between ascetic and worldly values (including social values) is dealt with and mitigated.

This book is an interpretation of a Svetambar Jain tradition from the standpoint of the theoretical ideas sketched out earlier. I use the term interpretation deliberately. I wish to emphasize the fact that I have not attempted to write anything resembling a complete ethnography of either a religious way of life or of the way of life of a localized religious community. Instead, I have concentrated on a particular analytical problem and have pursued it wherever it has taken me. The trail I followed led me to discussions of Jainism and Jain affairs with many individuals, to ritual performances, to texts and other writings, and to various temples and sacred centers. But there are important areas of Jain life to which it did not lead me, and which are therefore not treated—or are not fully treated—in this book. For example, lay and mendicant ascetic praxis is only touched upon. In this respect the present study is a narrow one. I believe that my findings are certainly relevant to any general understanding of Jain life, but I do not present them as constituting such an understanding.

The materials on which the book is based were obtained by means of observations of rituals and other aspects of Jain life, from formal and informal interviews, and also from a wide variety of writings. My use of written sources is, in fact, a good deal more extensive than is common in ethnographies. It needs to be stressed that the conventional model of ethnographic research—participant observation and conversation—is not fully adequate in the case of the Jains. The level of edu-

cation and intellectual sophistication in Jain communities is high. Jain traditions have always been productive of written materials, and this includes not only texts in classical languages but currently many works in modern Indian languages and even English. The books I encountered in the homes of my respondents were often well thumbed, suggesting that they are indeed read. Anyone who would understand Jain life must read what Jains themselves read.

My contact with written materials developed as a natural consequence of following the trail of my inquiry wherever it might lead. In the course of my inquiries individuals would place books and other written materials in my hands as relevant to my questions, and in this sense my interest in literature emerged from the fieldwork situation itself. The writings in question included ritual manuals, texts designed to be recited or sung in rituals, published discourses of ascetics, and compilations of caste and clan histories. These materials, mostly written in Hindi, played a part in my investigation somewhat like that of passive "informants." To the extent that I used these writings, one might say that the vantage point of this study hovers somewhere between the informant-oriented, ground-level ethnographic study and the loftier bird's-eye view of some textual scholarship.

The book starts with an analysis of basic ritual roles. Chapter One utilizes a detailed account of a complex rite of worship as a way of introducing the Jain concept of what constitutes a proper object of worship. This rite tells a story, and the story it tells defines with special clarity what it means to be worthy of worship in the Jain sense. To be worthy of worship is to be an ascetic, and the Tirthankar's life—which is what the text of the rite is about—epitomizes ascetic values. The chapter then turns to an account of Jain cosmography, cosmology, and biology; here we see a world portrayed in which only the most radical asceticism makes intellectual and moral sense. The chapter concludes with a brief discussion of living ascetics, that is, the monks and nuns who most directly exemplify Jainism's ascetic values.

Chapter Two turns Chapter One around; now our concern is the role of the worshiper, as opposed to the object of worship. The chapter begins with an account of a ritual that illustrates the role of the worshiper; this leads to a discussion of the nature of Jain deities—as opposed to Tirthankars—and also to the metaphor of kingship, which emerges as a central feature of this Jain tradition. A Tirthankar is someone who might have been a worldly king but who became an ascetic and spiritual king instead. A Jain layperson is someone who venerates

ascetics, and who, in so doing, becomes a kind of king. But because of the tradition's unrelenting commitment to ascetic values, this metaphor proves unstable. When the Tirthankars are worshiped there is an inherent and apparently unresolvable tension between otherworldly and worldly values, and worldly values must always give way in the end.

Chapter Three narrows the book's focus to Jaipur and those Svetambar Jains who are associated with the ascetic lineage known as the Khartar Gacch. The chapter introduces the cult of the Dadagurus. In this cult the dominant image of the relationship between worshiper and object of worship is redefined and given a somewhat different symbolic surround. It is certainly a form of worship that is attuned to Jainism's central values, for the objects of worship are Jain ascetics; but in this cult asceticism supports, instead of challenging, the worldly aspirations of devotees. I characterize this cult as a ritual subculture because, although the ritual patterns it employs are distinctively and recognizably Jain, it nonetheless differs in significant ways from the dominant ritual culture focused on worship of the Tirthankars.

The Dadagurus not only serve as a connecting point between the worldly aspirations of lay worshipers and ascetic powers associated ultimately with the Tirthankars, but they also provide a link between religious values and the structure of the contemporary Jain community. The link is seen in the origin mythology of Jain clans, and this is the principal concern of Chapter Four. The metaphor of kingship is again central; most of the Jains we see in Jaipur today are believed to be the descendants of warrior-kings who were tamed and vegetarianized by great ascetics of the past.

Chapter Five places Jain ritual culture in a wider South Asian context. The focus of this chapter is on patterns of religious gifting, and we learn that from this standpoint Jain ritual culture is not truly distinctive. Although some Hindu ritual cultures exhibit striking differences from Jain patterns, at least one Hindu ritual culture seems very similar to that of the Jains. Among other things, this discovery raises serious questions about conventional methods used in classifying South Asian religions. The materials surveyed suggest that, from the standpoint of ritual culture, there is no clear boundary between Jain and Hindu traditions. Instead, we are dealing with a series of logical permutations of the relationship between the roles of those who worship and those who are worshiped in South Asia.

Chapter One

Victors

We begin with the namaskar mantra . This utterance, also known as the mahamantra or the navkar mantra , is Jainism's universal prayer and all-purpose ritual formula. It is hardly possible to exaggerate its importance. It is repeated on most ritual occasions, and many Jains believe it to contain an inherent power which, among other things, can protect the utterer in times of danger. When, in the summer of 1986, I arrived in Ahmedabad to study Jain rituals, a Jain friend who was assisting me in my research insisted that my first order of business should be to commit the namaskar mantra to memory. One of my most pleasant memories of Jaipur is of an elderly friend pointing with pride to his small grandson who, hardly yet able to talk, had memorized the mantra . A somewhat more disquieting memory is of yet another friend who responded to an allusion to my own nonvegetarian background by hastily mumbling the mantra under his breath.

In essence it is a salutation (namaskar ) to entities known as the five paramesthin s, the five supreme deities.[1] These beings are worthy of worship, and it is crucial to note that these are the only entities the tradition deems fully worthy of worship. They are, in order, the arhat s ("worthy ones" who have attained omniscience; the Tirthankars), the siddha s (the liberated), the acarya s (ascetic leaders), the upadhyayas s (ascetic preceptors), and the sadhus (ordinary ascetics). The mantra 's importance to us is that it is a charter for a type of ritual, singling out a certain class of beings as proper objects of worship. These beings, we see,

are all ascetics.[2] This is the fundamental matter: Jains worship ascetics, and this is the most important single fact about Jain ritual culture.

This chapter deals with ascetics as objects of worship among the Jains. Who are they? What qualities single them out from other beings? What makes them worthy of worship? We begin addressing these questions by examining the text of an important ritual. The namaskar mantra lists the arhat s, by which is meant the Tirthankars, as foremost among those who are worthy of worship. The ritual with which this chapter begins is itself an example of Tirthankar-worship. Its text, moreover, tells us something of why the Tirthankar is worthy of worship. After examining this rite, we will consider ideas about the cosmos that inform the rite, and move finally to a discussion of living ascetics as objects of worship.

The Lord's Last Life

Most of my Jain friends and acquaintances in Jaipur were businessmen, many in the gemstone trade. These men were not, by and large, sophisticated about religious matters and did not pretend to be. They were men of business and masters of their craft. They had little time or inclination to worry about or debate the fine points of Jainism.

Nor were they usually very observant beyond a certain minimum. Of course they were all vegetarians. Although I frequently heard the allegation that many men of their sort ate meat on the sly, I saw absolutely no evidence of this. Nonetheless, despite the constant exhortations of ascetics, most did not strictly adhere to such rules as the avoidance of potatoes, and few indeed avoided eating at night. Avoiding vegetables that grow underground (which are believed to be teeming with life-forms) and not eating at night (so as not to harm creatures that might fall into the food) are generally regarded as indices of serious Jain praxis. Most were not daily temple-goers, although I believe most of them knew at least the rudiments of temple procedures. But in spite of a certain amount of behavioral and ritual corner-cutting, by any reasonable standard these men were serious Jains.

One good friend, then a youngish bachelor in whose gem-polishing establishment I spent many an hour, is exemplary of this whole class of men. He knows how to perform the basic Jain rite of worship (the eightfold worship, to be discussed in Chapter Two). He visits a temple about once a week. He usually does so for darsan , for a sacred viewing

of the images, not to perform a full rite of worship. He used to go to an important regional pilgrimage site (at Malpura near Jaipur) every month on full moon days, although this has dropped off because of the pressures of business. He fasts only once a year on the last day of Paryusan, the eight-day period that is the most sacred time of the year for Jains. He performs the expiatory rite of pratikraman on this day also. He certainly does not pretend to live the life of an ideal Jain layman, but he nevertheless identifies strongly with Jainism and holds its values and beliefs in the highest possible esteem.

As do many other men of his general class, condition, and age, he comes from a family in which women are highly observant and usually far more so than the men. His mother performs the forty-eight-minute contemplative exercise called samayik and visits a temple daily. She fasts four times a month, and on fasting days she performs the rite of pratikraman . She has not eaten root vegetables from the time of her birth, and for at least thirty years has not taken food at night. The wife of one of his six brothers follows the same strict pattern as her mother-in-law. His other sisters-in-law visit the temple once or twice a week and fast approximately once a month; they would probably do more, he said, were it not for the responsibility of young children.

And here is the mystery. Even in this rather observant family, my friend told me, the topic of liberation (moks ) from the world's bondage simply never comes up. He added that he does not even remember anyone ever mentioning the word; it just was not part of the family discourse. He himself hardly gives any thought to liberation. Indeed, in response to my queries he ventured the opinion that liberation is really "not possible" at all (meaning, I believe, for people in his own position). In order to attain liberation, he said, you have to renounce the world and devote yourself to spiritual endeavors. "But we," he said, "have our businesses to attend to." He went on to state that most Jains do not actually know what liberation is, and visit temples solely for the purpose of advancing their worldly affairs.

The matter, however, is more complex than my friend's remarks might suggest. Let me say at once that to some degree he was exaggerating, probably for pedagogical effect. For example, the issue of liberation would not normally arise in a family context, but the same individuals might well speak of liberation in more specifically religious contexts. Still, it remains true that the religious lives of most ordinary lay-Jains are not liberation-oriented. Even women's fasting—which is often spectacular and certainly evokes the image of the moks marg (the

path to liberation)—seems often, and perhaps mostly, to be motivated by the desire to protect families, to achieve favorable rebirth, or even to gain social prestige.[3] 1 found a general awareness and understanding of the goal of liberation among Jains with whom I discussed the matter, but liberation tends to be seen as a very remote goal—not for now, not for any time soon.

But at the same time, it is also generally understood that although rituals, fasting, and other such religious activities generate merit (punya ) that will lead to worldly felicity, the goal should be liberation. This is certainly the view promoted by Jain ascetics in their sermons, and it is reasonably well understood by the laity. Many Jains say, as my friend does, that other Jains engage in ritual purely to advance their worldly affairs. But the point, of course, is that one should not be so motivated; one should really be seeking liberation. Given all this, we are presented with a puzzle. Just what is the relationship between liberation and the lives and aspirations of lay Jains?

This puzzle is perhaps nowhere more evident than in the major periodic rites of worship. These rites are, in fact, a vital domain of religious activity for men such as my friend. As Josephine Reynell points out (esp. 1987; see also Laidlaw 1995: Chs. 15-16), there is a basic division of ritual labor among temple-going Svetambar Jains: women fast, while men—too immersed in their affairs to do serious fasting—make religious donations (dana ; in Hindi, dan ). A major field for religious donations is the support of important periodic rites. These are often held in conjunction with calendrical festivals and also on the founding anniversaries of temples. They are frequently occasions for the display of great wealth. Truly startling sums are often paid in the auctions held to determine who will have the honor of supporting particular parts of the ceremony or of assuming specific ceremonial roles. This aspect of sponsorship seems to function as a public validation of who's who in the wealth and power hierarchies of the Jain community. The ceremonies supported by this cascade of wealth are typically sumptuous, lavish occasions—full of color and suggestions of the abundant wealth of the supporters. They seem to have little to do with liberation from the world's bondage.

And yet here is the paradox. If we peel away the opulence and glitter from these occasions we discover that liberation is there, right at their heart. At the center of all the spending, the celebration, the display, the stir, is the figure of the Tirthankar. He[4] represents everything that the celebration is apparently not, for he is, above all else, an ascetic. His

asceticism, moreover, has gained him liberation from the very world of flowing wealth of which the rite seems so much a part. Liberation and the asceticism that leads to liberation are thus finally the central values, despite the context of opulence. Wealth is not worshiped; wealth is used to worship the wealthless.

We now look more closely at an example of such a rite. The example I have chosen is not only a rite of which the Tirthankar is the object; it is also a rite that, in a kind of doubleness of purpose, explains why the Tirthankar is an object of worship.

A Major Rite

The end of the year 1990 was a troubled time in Jaipur. In many north Indian cities the autumn months had been marred by agitations against the national government's decision to implement a far-reaching policy of job reservations for lower castes. In Rajasthan these same months had seen a lengthy and exasperating bus strike. Then, in late October, there were deadly communal clashes between Hindus and Muslims in Jaipur provoked by the efforts of Hindu nationalists to demolish a mosque in Ayodhya, one supposedly built on the site of Lord Rama's [5] birth, and to replace it with a Hindu temple. By December, Jaipur was still a very uneasy city, and for this reason the Jain festival of Paus Dasmi was not celebrated with the usual éclat.

Paus Dasmi is an annual festival celebrated by Svetambar Jains in commemoration of the birth date of Parsvanath. Parsvanath is the twenty-third Tirthankar of our region of the cosmos and era, and is one of the most greatly revered of the Tirthankars. He was born on the tenth day (Dasmi) of the dark fortnight of the lunar month of Paus (December/January), which is why the festival is called Paus Dasmi. In 1990 this day occurred on December 11. In Jaipur this festival is normally the occasion for a major public display of religious symbols. In ordinary years, on the day before Paus Dasmi a portable image of the Tirthankar is taken in public procession from a large temple in Jaipur's walled city to a temple complex at a place called Mohan Bari on Galta Road.[6] There, on the morning of the birthday itself, the image is worshiped, and then on the afternoon of the same day the image is returned to its original temple in another public procession. But in December of 1990 this was not to be. Because of the city's troubles, no permit for the procession could be obtained. Still, at least the basic rite of worship could be performed, and it is this performance that is described in what

follows. It was perhaps fortunate for me that it was celebrated in a relatively small way, for this gave me a chance to observe its performance with special closeness.

The rite is an example of a type of congregational worship commonly known as mahapuja , a "great" or "major" (maha ) "rite of worship" (puja ). Such rites, which come in several varieties, are commonly performed by Svetambar Jains on special occasions in both Ahmedabad and Jaipur. Most of them are directed at the Tirthankars, but I once witnessed a mahapuja for the goddess Padmavati (a guardian deity, not a Tirthankar) in Ahmedabad, and the congregational worship of certain deceased ascetics who are not Tirthankars, figures known as Dadagurus, is central to Svetambar Jainism in Jaipur. The occasions for these rites are quite various. Sometimes, as in the present case, they are performed in conjunction with calendrical festivals. The consecration anniversaries of temples are celebrated by means of these rites, and they are sometimes held to inaugurate new dwellings or businesses. Congregational worship of the Dadagurus is often held in fulfillment of a vow (see Chapter Three). A rite called the antaraynivaranpuja (the puja to "remove obstructive karmas ") is frequently performed on the thirteenth day after a death.

The specific rite to be discussed here belongs to a class of rites known as pañc kalyanakpujas . The expression pañc kalyanak means "five welfare-producing events," and refers to five events that are definitive of the lives of the Tirthankars. Although the Tirthankars have different individual biographies, the truly significant events in the lifetime of each and every Tirthankar are exactly five in number and are always precisely the same.[7] They are: 1) the descent of the Tirthankar-to-be into a human womb (cyavan ),[8] 2) his birth (janam ), 3) his initiation as an ascetic (diksa ), 4) his attainment of omniscience (kevaljnan ), and 5) his final liberation (nirvan ). A pañc kalyanakpuja is a rite of worship celebrating the five welfare-producing events—the five kalyanaks —in the life of a particular Tirthankar.[9] Five-kalyanakpujas are very important as a class of rites, a fact that reflects the importance of the kalyanaks as cosmic events. Five-kalyanakpujas are often performed as part of the ceremony that empowers the images in Jain temples, and this suggests that the Tirthankars' kalyanaks have left a residue of welfare (kalyan ) in the cosmos that can be focused in images and mobilized by rituals in the service of worshipers.

Every major Jain rite of worship is based on a specific text that carries its distinctive story line or rationale. In the case of a pañc kalyanak

puja of the sort to be described here, the story line recounts the five kalyanaks as the key episodes in the biography of a specific Tirthankar. Such texts are always authored by ascetics. The text of the present rite was written by a Khartar Gacch monk named Kavindrasagar (1905-1960) whose chief works include a number of well known pujas . The type of Hindi in which the text is written is easy for participants to understand.

The particular rite performed on Paus Dasmi celebrates the five kalyanaks of Parsvanath. It is, accordingly, called the parsvanathpanc kalyanakpuja , and its story line is an account of the five kalyanaks as they occurred in Parsvanath's own particular career. Participants sing songs from the text that recount and praise each of Parsvanath's five kalyanaks , and at the conclusion of each set of songs certain prescribed ritual acts occur.[10] Sometimes favorite devotional songs not in the text are added. The rite thus consists of five separate groups of ritual acts, each preceded by a group of songs. It should be understood that most participants in such rites are at least minimally conversant with these songs, and some will know some of them or parts of them by heart. The text is as central to the rite as the ritual acts that accompany its singing. The ritual acts (to be described below) are completely standard in the sense that more or less the same ones occur in all rites of this sort. It is the text that embeds the ritual acts in a narrative that differentiates the significance of one type of rite (in this case the parsvanathpañc kalyanakpuja ) from others.

The spirit in which the songs are sung is also very important. The rite is seen as an expression of devotion (bhakti ). For a rite of this sort to be successful, the songs should be sung with gusto and feeling; they should express, that is, the proper spirit (bhav ). Typically, rites of this kind start slowly with a limited number of participants. As time passes, more participants arrive, and at the end—if all is well—the site of the ceremony will be packed with lustily singing devotees. In the case of the particular rite described here, the troubled context kept attendance down, but the singing was spirited.

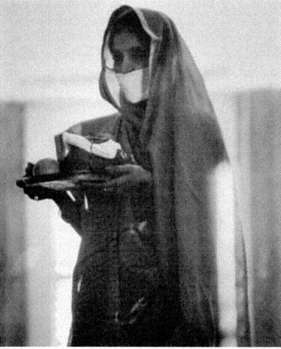

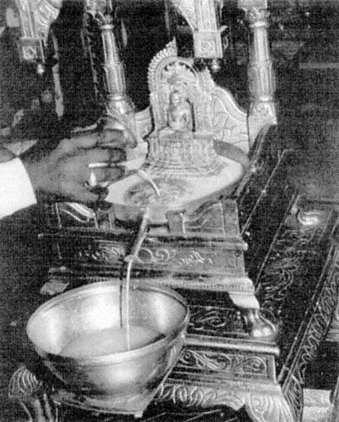

The ritual acts are the responsibility of a limited number of individuals who are bathed and wearing clothing appropriate for touching sacred images (see Chapter Two). These I call "puja principals." They stand, often in husband-wife pairs, holding a platter containing offerings while the songs appropriate to a given segment of the rite are sung; when the appropriate moment comes they perform the required actions

Figure 1.

A puja principal holding offerings in

Jaipur. Note the mouth-cloth designed to prevent im-

purities from being breathed on the image.

(see Figure 1). Because of the troubled atmosphere in the city, in this case the temple's pujari (ritual assistant) was the sole puja principal; normally there would have been several drawn from the city's lay community. The other participants serve as both singers and as a sort of audience (though they are not pure spectators). Remaining seated, they sing the puja's verses and witness the puja principals' acts. In the case in question about a hundred participants of this sort were on the scene by the ceremony's end.

We thus see that the role of worshiper is actually manifested in two ways in rites of this sort. The puja principals are in physical contact with the image; others are at an audience-like distance. In a sense the puja principals "do," while the others felicitate what is "being done." Jains believe that one's approval (anumodan ) of another's good deed is spiritually and karmically beneficial, and the division of ritual labor

seems to capitalize on this concept; by means of vocal participation an indefinite number of individuals can partake of the benefits of the rite.[11] Svetambar Jain ritual culture is of the do-it-yourself sort; there is no role for priestly mediators, and this would seem to inhibit any sort of congregationalism. We see, however, that the differentiation of the worshiper's role into two modes allows for a strong congregational emphasis.

What follows is an abstracted account of the rite as I saw it performed in 1990 with a special emphasis on the text. The focus of worship was a small metal image of the Tirthankar and a metal disc on which the siddhcakra had been inscribed.[12] These items were placed atop a stand that was stationed at the entrance to the main shrine at Mohan Bari. Participants sat in the temple's courtyard, with men to one side and women to the other (the standard arrangement). In front of this stand with the image was a low table on which five small flags had been placed in a row. Svastiks (executed in sandalwood paste) marked the positions at the foot of each flag where offerings were deposited as the ceremony progressed.

Parsvanath's Story

The puja of Parsvanath's five kalyanaks begins with the cyavan kalyanak , his descent from his previous existence as a god into a human womb.[13] The text for this sequence consists of three songs that recount Parsvanath's nine births prior to his final lifetime. This narrative centers on Parsvanath's relationship with Kamath, who is Parsvanath's transmigratory moral alter. Kamath's defects reverse Parsvanath's virtues, and Parsvanath's virtues provoke Kamath again and again into the gravest sins. The story of how this fateful relationship began is not covered in the text, but is well known to the rite's participants. Marubhuti (who will become Parsvanath in a later birth) and Kamath were once Brahman brothers. Marubhuti was a paragon of virtue who had accepted Jainism and spent his time in meditation and fasting. Kamath, much given to sensual pleasures, committed adultery with Marubhuti's wife. Marubhuti spied on the couple and reported Kamath's misdeed to the king. Kamath was punished, and Marubhuti was filled with regret. Marubhuti came to Kamath to beg forgiveness, and, while he was bowing, Kamath killed him with a stone.

It is at this point that the narrative begins. "Crooked Kamath was

attached to sensual vices," says the opening verse, "he killed his brother Marubhuti." As the text (which I summarize) continues, we learn how Marubhuti took his next birth as an elephant and was returned to the piety of his previous life by the king, who in the meantime had become an ascetic. Taking the form of a kukurt serpent (part snake, part cock), Kamath then murdered him again. Marubhuti was reborn as a god, while Kamath went to hell. In his next birth Marubhuti became a king named Kiranveg. He renounced the world, only to be murdered again by Kamath in the form of a snake. Marubhuti now became a god in the twelfth heaven, while Kamath descended to the fifth hell. In his next birth Marubhuti was a king named Vajnabh. He again renounced the world, and Kamath, in the form of a Bhil (a member of a particular tribe), killed him with an arrow. Marubhuti then became a god in one of the highest heavens, and Kamath descended to the seventh hell.