1. War, State, and Markets in the Middle East

The Political Economy of World Wars I and II

2. Guns, Gold, and Grain

War and Food Supply in the Making of Transjordan

Tariq Tell

In 1924, a “commentator on Middle Eastern affairs” who wrote under the pseudonym Xenophon, remarked that “of all the provinces of the vast Turkish empire left disorganized at the end of the World War, there was none so abandoned as that part of Arabia now known as Transjordania.” Transjordan had evolved from the wreckage of World War I, conjured up by Churchill and Lawrence in 1921 as part and parcel of the division of the Fertile Crescent between Britain and France. Yet if war, in a literal sense, made modern Jordan, the relationship between war making and state making along the desert marches of southern Syria was quite different from that envisaged by Charles Tilly. Once the “Great Arab Revolt” launched by Hussein ibn ‘Ali, the sharif of Mecca, spilled over from the Hijaz in July 1917, tribes as well as states waged war and the power of the Ottoman state receded. By December 1918 the revolt had undermined the Ottoman order and ensured that an upsurge of tribalism, rather than an increase in “stateness,” was Transjordan’s legacy from the war to end all wars.

If the war years did little to build a Jordanian state, they did much to cement the claims of Hussein and his sons to leadership of the nascent Arab Movement. The Arabist pretensions of the Hashemites have in turn ensured that Jordan’s official historians chronicle the transition from Ottoman rule in patriotic terms.[1] Hussein’s revolt is seen as the culmination of the Arab Awakening, and its march on Damascus is viewed through a nationalist lens. Typically, it is argued that Transjordanians gave spontaneous and absolute loyalty to the Hashemites, that most of them “actively supported the revolt,” and that by enlisting in its ranks in the “thousands” they were “a major factor in the successful outcome of the revolt.”[2] The “Arab Movement” is assigned a crucial role in the creation of Transjordan. If the country’s borders were fixed by bargaining by the Great Powers after the war, “its national character was preserved by Arab effort.”[3]

The aftermath of World War I did much, however, to devalue the claims of Hashemite Arabism. Hussein launched his uprising with British prompting, yet the end of the war saw Britain reneging on the promise of Arab independence held out by Hussein’s famous correspondence with MacMahon. Britain’s “perfidy” and the accommodation of the sharif’s sons ‘Abdallah and Faisal to its tutelage after 1921 has cast doubt on the credentials of the revolt. Arab radicals came to condemn its imperial provenance and to see it as a reactionary affair representing narrow and dynastic interests that in practice delivered the Fertile Crescent to colonial rule.[4] Sympathetic historians argue that to give credit to the Transjordanian tribes for the success of the revolt is a “historical blunder.” Instead the tribespeople “abided by decisions of their shaykhs, who usually joined hands with the side that offered them the more profitable terms. . . . Neither the ordinary bedouin nor his shaykh were able to appreciate the wider meaning of events and the historical significance of the Arab revolt.”[5]

Contending views of the transition from Ottoman rule remain central to ideological politics in contemporary Jordan.[6] Yet neither the Hashemite historians nor their protagonists provide an adequate understanding of Arabism as an ideology, of early Arab nationalism as a social movement, or of how the context of war conditioned the course of Hussein’s revolt. The politics of Arabism are portrayed as an affair of notables and nationalists, with a corresponding neglect of non-elites and rural actors.[7] The Arab Movement is imbued with “an immutable and singular identity,” wherein Arab nationalism, rather than being reinvented or diversely imagined by different social groups, is spontaneously recovered and diffused among the population at large by the conjuncture of Turkish oppression and Sharifian example.[8] As a result, narratives of the revolt impose an unwarranted coherence on what was always a multilayered and conflictual movement and give scant attention to the motives of the tribesmen who served as its foot soldiers, or to the social and material forces that led them to rally to the Sharifian cause.

This chapter seeks to recover the contingent and contested qualities of the revolt through a microhistorical focus on the local dynamics through which war making shaped the trajectory of Transjordanian state formation. In the account presented here, it is precisely the social and economic conditions of war, local strategies, and material incentives, rather than the high politics of British treachery and Hashemite ambition, that hold center stage. It was, in particular, variation in the extent to which social groups (tribes) were vulnerable to hunger as a result of wartime shortages that shaped patterns of participation in the revolt. Tribes whose food security was at risk were responsive to the material incentives provided by the leaders of the revolt in exchange for their commitment to participate. Where food security was less vulnerable to wartime conditions, and where Ottoman forces controlled the markets on which tribal units depended for their subsistence, tribal leaders displayed a greater reluctance to join forces with the anti-Ottoman campaign of Sharif Hussein and his associates. In other words, it was the material incentives or disincentives associated with a political commitment to the anti-Ottoman campaign of Hussein—not the ideological claims of notables and nationalists—that led tribes to participate in the revolt or withhold their support.

East of the Jordan River, these factors were played out in the context of a revitalized Ottoman administration that had been consolidating its hold on Transjordan since the mid-nineteenth century, co-opting or importing local proxies, and greatly expanding the local presence of the Ottoman state.[9] The contours of this resurgent order were obscured from contemporaries like “Xenophon” by the destructive legacy of the war years and concealed from more recent commentators by an Arabist historiography that for too long dismissed or distorted the significance of four centuries of Ottoman rule.

| • | • | • |

Tribe and State in Transjordan Under the Ottomans

In broad terms, the history of Ottoman Transjordan confirms the veracity of Zeine’s comment that “the Arabs up to the reign of Abdul Hamid (1876–1908) suffered not from too much Turkish government but from too little.”[10] Until the second half of the nineteenth century, Ottoman intrusion into this dusty corner of Bilad al-Sham did not go beyond ensuring the safe passage of the annual Hajj caravan. Ottoman officials appeared in the country in significant numbers only during the twenty or so days it took the pilgrimage to traverse the distance between southern Syria and the borders of the Hijaz. Such imperial influence as existed at other times was exercised by the local proxies of Ottoman governors or by tax collectors in their intermittent forays from Damascus and other towns of southern Syria.

In the absence of routinized central authority, Transjordan was dominated by a local order, “a social, economic and cultural fusion of nomads and peasants” created by the interaction of bedouin and villager along the frontier of settlement in southeastern Syria.[11] Although southern Syria’s location at the periphery of imperial control has thrown a veil of ignorance over many aspects of the local order, tribal histories, anthropological work, and recent writings on the extension of “the frontier of settlement” allow the construction of a provisional picture of a tribalized society that lacked significant urban centers and was dominated by parochial loyalties and the ideology of segmentary kinship.[12]

The population divided broadly into bedouin (literally, dwellers of the steppe, or badia) and cultivators, or fallaheen. Local sources list the bedouin by tribal affiliation but also refer to them generically as al-‘arab or sukkan al-khiyyam, the tent dwellers. Apart from their mode of residence, the bedouin were a heterogeneous group ranging from camel nomads who drove their flocks eastward to winter in the Wadi Sirhan and Jabal Tubayq, to more sedentary tribes who combined sheepherding with scattered cultivation.[13] The general pattern was for the more mobile camel-herding tribes—various factions of the ‘Anayza and the Bani Sakhr in the north and center of Transjordan, the ‘Adwan in Balqa, and the Huwaytat in the south—to dominate the more sedentary ones. An annual tribute, khuwwa (literally, brotherhood payment), was exacted from the weaker tribes in return for protection against raiding (ghazuw). For the more powerful bedouin tribes, such as the Bani Sakhr and the Ruwalla (or the Harb, Billi, and Bani ‘Attiyyah further south and in the Hijaz), this was supplemented by the levying of protection money (surrah) from the Ottoman authorities in return for the safe passage of the Hajj caravan, which also formed the main market for the bedouins’ camels.

The bedouin also collected khuwwa from the fallaheen. Until the mid-nineteenth century, the double burden of Ottoman taxation and the exactions of the bedouin restricted sedentary cultivation to the hills of ‘Ajlun and the town of al-Salt in al-Balqa. While the cultivators dwelt in stone villages and caves rather than tents, they were everywhere tribal. In ‘Ajlun the villagers were organized into subdistricts (nahiyyats), each headed by the locality’s most powerful clan: the Shraydah in Kura, the ‘Utum and al-Farayhat in ‘Ajlun and al-Mi‘radh, the Khasawnah and Nusayrat in Bani ‘Ubayd, the ‘Azzam in al-Wustiyyah, the ‘Abaydat in Bani Kananah, the Rusan in al-Saru, and the Zu‘bi tariqah (Sufi religious order) in Ramtha. The people of al-Salt, al-Saltiyyah, presented a united front to outsiders but divided internally into two major tribal factions: al-Akrad headed by the ‘Arabiyyat clan, and al-Harah headed by the ‘Awamlah.[14]

Where influential shaykhs or shaykhly clans could harness their tribal followings to gain control of local tax collection or to monopolize the escort of the annual Hajj caravan, chiefdoms emerged—notably under the Shraydah in Kura, the Majali in Karak, the Adwan and Bani Sakhr al-Fayez clan in Balqa—to fill the vacuum left by the absence of effective Ottoman control.[15] However, only the Ruwalla of the great camel-herding tribes of the Syrian Desert passed through Transjordan, and the power of the local chiefs remained limited in comparison to the larger tribal emirates of northern Arabia. As a result the local order in Transjordan remained weak and fragmented, subject to the ebb and flow of actions by contending power centers outside its borders—on the one hand, the Wahhabi and Rashidi emirates in the Arabian interior, and on the other, the Ottoman pashas or quasi-autonomous tax farmers in Damascus, Acre, and Sidon.

It was the second set of influential groups that began to gain the upper hand after the middle of the nineteenth century with the arrival in Transjordan of the centralizing influences of the tanzimat. Between 1851 and 1893, a direct Ottoman presence was established in forts and outposts stretching from Irbid to Aqaba, and an armed expedition in 1867 compelled the submission of the Balqa bedouin, collected unpaid taxes, and ended the extraction of khuwwa from the villagers. After 1870, Ottoman authority was reinforced by the arrival of settlers loyal to the new order. Caucasian refugees were implanted along the frontiers of settlement in ‘Ajlun and the Balqa, and Turcoman villages were established at Lajjun and al-Hummar. As imperial authority consolidated itself, merchants and migrants from Damascus and Palestine flocked to Irbid and al-Salt, and their enterprise turned Circassian villages like Amman and Jarash into significant market towns.

The integration of Transjordan into the grain export trade of the Syrian interior provided the economic foundations of the new order. Consular sources report wheat coming to Jerusalem from beyond the Jordan River as early as 1850, and by 1860 grain farming had led to the emergence of a distinct landowning elite among the Fayez clan of the Bani Sakhr.[16] The upward trend in wheat prices between 1840 and the end of the Crimean war boom, and the dwindling number of pilgrims using the overland route to Mecca, may have been the main forces encouraging the growth of grain farming before the establishment of direct Ottoman control. The return of the Ottoman state provided an additional (if indirect) boost to grain farming. The collection of tax arrears in al-Salt created excess demand for liquidity and, therefore, an opportunity for merchants to accumulate capital through money lending. Merchants and money lenders anxious to integrate grain production and trade invested the proceeds of usury in land, consolidating great estates and thereby cementing the transition to commercial agriculture in the Balqa.

Commercialization brought rapid growth in agricultural production and exports. By 1894 the newly created sanjaq of Ma‘an (which included the districts of al-Balqa and al-Karak) was exporting some 12 million francs worth of agricultural goods, including wheat, barley, and livestock products such as samn (ghee). Further north, ‘Ajlun was integrated into the export agriculture of the Hawran. By 1901, there were a million acres under cereal cultivation in the district, and over 3 million bushels were exported from the area. In all, ‘Ajlun’s production amounted to over one-third of the Hawran’s combined grain harvest.[17]

It is possible to document a flow of land transfers in the area north of the Mujib (Moab) valley from the 1880s onward—in particular the communal pastures of the bedouin—from the indigenous tribespeople to merchants and settlers. Moneylenders and bureaucrats acquired large estates in the Balqa, the Jordan Valley, and the environs of Irbid. However, how much land the indigenous tribespeople lost is unclear. The 1880s also saw the emergence of the “bedouin plantation village”—land registered in the names of influential shaykhs and farmed by Egyptian and Palestinian sharecroppers.[18] Both the Balqa and ‘Ajlun witnessed “indigenous” movements of colonization that kept land in tribal hands. Madaba and a number of villages in the environs of al-Salt were settled by local Christians in the 1870s, and a section of the Khasawna clan took possession of al-Nu‘ayma after being forced from their homes by the Christians of al-Husn.

On the available evidence it seems that the extension of the Ottoman frontier in northern Transjordan generated a dual system—with commercial estates and settler villages existing uneasily alongside indigenous tribes.[19] The tensions in the system were apparent in tax revolts and in inter- and intratribal feuding that did not die down until the 1880s. However, overt resistance to the new order subsided in the following decades as the infrastructure of Ottoman power in Transjordan was completed with the registration of land and property, and with the building of a communication network that culminated in the passage of the Hijaz Railway through the country in 1906.

| • | • | • |

Transjordan Between Ottomanism and Arabism

The Ottoman order in north and central Transjordan seemed secure by the first decade of the twentieth century. A permanent Ottoman presence had been established in ‘Ajlun and Balqa for two generations or more. It was now buttressed by the construction of the Hijaz Railway, by a dense network of roads and telegraphs, and by merchants and migrants loyal to the Ottoman state. The old tribal order survived at the local and village level, whether in the form of customary land tenures—which persisted despite registration in the Ottoman tapu—or an enduring loyalty to tribe and clan.[20] Nevertheless, both the cultivators and bedouin were enmeshed in the grain export economy of southern Syria. The economic surplus this generated funded the Ottoman administration and allowed an embryonic elite to emerge from the bedouin aristocracy and the larger merchant landowners.[21] Whether as members of town councils or as local district officers (qaimmaqam), the new tribal landlords acted as proxies for Ottoman rule.

South of the Mujib, direct Ottoman rule was both more recent and less secure. The Ottomans had to maintain the surrah to prevent the bedouin from attacking the Hijaz Railway.[22] With the exception of a small Turcoman presence at Lajjun and the temporary inflow of Damascenes into Ma‘an during the construction of the railway, Ottoman rule lacked the reliable auxiliaries available further north in settlements such as Amman or Jarash. Except on the Karak plateau, the agricultural surplus was meagre, and even here it was used to supply the surrounding bedouin rather than for export. The town’s merchants—for the most part migrants from Damascus and Hebron—were little more than shopkeepers and never attained the wealth or status of their counterparts in al-Salt.

Therefore the local order was largely intact in southern Transjordan when the accession of the Young Turks in 1908 brought new efforts to centralize the Ottoman state. Having subjugated the Jabal Druze in the summer and fall of 1910, an Ottoman force under Sami Pasha al-Faruqi moved south to impose conscription and disarm the population in ‘Ajlun. While al-Faruqi’s troops faced little resistance north of the Mujib line, attempts to impose the same measures in Karak brought protests, pleas, and petitions from the local shaykhs. When these failed to move the authorities, a bloody uprising broke out in Karak that spread to Tafila and led to bedouin attacks on some of the stations on the Hijaz Railway. The revolt was led by the Majali, whose paramount shaykh, Qadr, fed the Karakis’ fears of conscription and disarmament and played on rumors that the Young Turk–led Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) intended to suspend payments to the bedouin along the Hijaz Railway.

The Karak revolt was eventually suppressed and its ringleaders imprisoned. However, al-Karak’s cause was taken up by the Arabist press in Damascus and in the Ottoman parliament, where Arab feeling was on the rise in reaction to the Turkifying policies of the CUP and where Tawfiq al-Majali, the town’s deputy to the Ottoman mab‘uthan (Ottoman parliament), moved in nationalist circles. Together with the participation of the surrounding tribes in sympathetic attacks on the railway, this has led some historians to interpret the Karak revolt in nationalist terms or to see in it a precursor of the Great Arab Revolt of 1916.[23] However, contemporary Arabists were for the most part separated by a considerable social and political gulf from the rebels of al-Karak. While the former were urban nationalists who sought a larger share in the Ottoman polity, the Karakis seemed wholly opposed to it. Their victims during the uprising were the town’s merchants, the hapless census teams, and such representatives of the Ottoman order as failed to find sanctuary in Karak’s citadel.[24]

The Karak revolt is better seen as the dying spasm of the local order, a doomed attempt of a tribal system to defend itself against an encroaching state. The Ottoman hold on the district was rapidly reestablished, and the Karakis for the most part remained loyal Ottomanists throughout the subsequent years of war and revolt. At least at the grassroots level, a similar antipathy to centralization marked the events leading to the Arab Revolt in the Hijaz in 1916. As was the case in Karak, a local elite manipulated tribal resistance to Ottomanism for its own ends. Hijazi localism, rather than Arab nationalism as understood in Damascus or Beirut, was the defining feature of Arabian politics between 1908 and 1916.

| • | • | • |

The Origins of the Arab Revolt: Ottomanism Versus Localism in the Hijaz

The late Ottoman Hijaz was an unlikely crucible for Arabism. The province was among the most backward in the Ottoman Empire. Its cities, steeped in ancient privilege and religious superstition, lacked the adversarial press, Arabist notables, and educated middle class that were the hallmarks of early Arab nationalism in Greater Syria or Iraq.[25] The Hashemite rulers of Mecca were at best late converts to Arabism and had as late as 1911 defied the weight of Arabist opinion by aiding the Young Turks’ suppression of the Idrisi’s rebellion in ‘Asir. In launching his revolt in 1916, the sharif of Mecca appealed to educated Hijazi opinion in traditional rather than Arabist terms. Hussein’s proclamations, and the articles and editorials of his mouthpiece Al-Qibla, accused the “atheistic” CUP of tampering with the Islamic legitimacy of the Ottoman state and called for the preservation of the ancient privileges of the Hijaz.[26]

Formed in a part of the Ottoman Empire “that was not at all nationalistic,” Hussein’s revolt therefore marked an “ironic beginning” to the Arab Movement. However, if Arabist doctrine had few converts in the Hijaz, the inhabitants of the province, whether townspeople or bedouin, were united in their hostility to the centralizing bent of Ottoman reform. Until 1916, local resistance found tangible expression in tax riots in the towns, as well as in bedouin opposition to the extension of the Hijaz Railway and the threat this posed to the surrah they received to protect the pilgrimage. By 1908 the opposition of the tribes had escalated to the point of a general tribal revolt that required six thousand troops for its suppression. Scattered attacks on the railway continued after the Young Turks came to power in 1908, and partial peace was maintained between 1909 and 1914 only by the prompt payment of subsidies to the Bani ‘Attiyyah, Harb, and Billi tribes and by the fortification of the railway’s main stations and watering points.[27]

The Hashemites shared the bedouins’ antipathy to Ottoman centralization. While publicly welcoming the Hijaz Railway, the incumbent clan of the Dhawi ‘Awn privately feared that it would provide Istanbul with the means to curtail their power in Mecca. The arrival of the Hijaz Railway in Medina in 1908 had proven to be a means for the consolidation of the Ottomans’ grip on the district. Medina and its environs were detached from the Hijaz vilayet and made into a separate mutasarrifiyyah (Ottoman subgovernate); and although bedouin affairs continued to be administered by a representative of the sharif of Mecca, it was the writ of the Ministry of the Interior and the local branch of the CUP that prevailed within the city walls.

The Young Turk revolution coincided with Hussein ibn ‘Ali’s accession to power in December 1908, and the confusion following the fall of Abdul Hamid allowed Hussein to consolidate his grip on Mecca. But within a year of his appointment, he had come into conflict with the CUP over the extension of the railway southward from Medina. Tensions with the Young Turks continued to escalate until 1914, when the latter began to promote the claims of a rival clan, the Dhawi Zayd, whose leader ‘Ali Haydar professed support for the railway’s extension to Mecca.[28] The outbreak of war brought matters to a head. It was the discovery of a Unionist plot to unseat him in January 1915 that seems to have convinced Hussein of the need to seek outside support in order to preserve his family’s position as autonomous rulers of the Hijaz.[29]

The realities of wartime Arabia dictated that Hussein turn to Great Britain, whose chief representative in Egypt, Lord Kitchener, had already rebuffed an approach from ‘Abdullah in 1914. As occupiers of Egypt, the Hijaz’s traditional source of grain and subsidy, the British had considerable influence over the rulers of Mecca. Cairo’s leverage was increased once Turkey joined the Central Powers and a naval blockade was imposed on the Red Sea and the trade routes into Kuwait. Moreover, the outbreak of war encouraged the British to conclude treaties with rival Arabian princes who could potentially threaten Hussein’s hold on the Hijaz. The latter included the Idrisi ruler of ‘Asir, whose followers had invaded Hashemite territory in 1915, and Ibn Sa‘ud, who had been in conflict with Hussein over the oasis of Khurma since 1910. British support promised to secure the Hijaz against these regional rivals, as well as provide the means to combat the intrigues of the Young Turks in Mecca.

Conducted by divergent power centers with competing interests, Britain’s wartime strategy in Arabia was, however, at best complex and most often confused. Grand strategists in Whitehall, aware of the need to conciliate the competing actors of the “Eastern Question” became more cognizant of the limits of British power and of the rival ambitions of Russia and France. The government of India, which occupied Aden and had responsibility for the Persian Gulf, favored the manipulation of local princes in order to pave the way for direct colonial control over Mesopotamia. Its “men on the spot”—Shakespeare until his untimely death in 1915, and H. St. John Philby—preferred to put their faith in Ibn Sa‘ud as the coming power in Arabia. As a result, it was only gradually that the Sharifian inclinations of Lord Kitchener and his protégés in Cairo and Khartoum began to influence imperial policy. In contrast to India, Cairo argued that Arabism could be harnessed to the imperial purpose and (no doubt more fancifully) that an alliance with a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad such as the Sharif Hussein could provide an antidote to the Ottoman call to jihad.[30]

In pursuit of these aims, the Arab Bureau in Cairo reinitiated contacts with the Hashemites. In the course of the famous “Hussein-MacMahon” correspondence that ensued, the sharif agreed to take up arms in support of the Allied war effort against the Turks. In return, Britain undertook to support Arab independence within boundaries broadly circumscribed by its secret agreement with France (the Sykes-Picot Agreement). The question of the compatibility of the two sets of undertakings has long exercised historians but need not detain us here. The most balanced assessments conclude that a pledge of Arab independence was given, but that it was not incompatible with Britain’s undertakings with the French.[31] Under the pressure of events, both the sharif and Britain chose to defer their differences until the postwar settlement, the contours of which were impossible to predict in 1916.

It seems clear, however, that the local politics of the Hijaz and Hussein’s dynastic ambitions, rather than Arabist sentiment, guided his preparations for the revolt. Rather than marking the culmination of the Arab Awakening, “it makes better sense to view the revolt as the death rattle of the traditional Ottoman order, the last gasp of a repetitive cycle of tension and struggle between Istanbul and the provincial elite.”[32] Conservative in its aims and traditional in its content, Hussein’s uprising marked an unlikely beginning for a new state system in the Arab east.

| • | • | • |

The Course of the Arab Revolt (I): The War in the Hijaz

It was nonetheless Hussein’s negotiations with the British in Cairo that brought the Arabist dimension of the revolt to the fore. Once the decision to break with Istanbul was made, the language of Arabism provided a useful tool for conducting a dialogue with a European power imbued with nineteenth-century notions of national self determination. Once the correspondence with MacMahon raised the possibility of Sharifian rule in Syria and Iraq, Arabism also offered a basis for legitimizing a new realm outside the traditional confines of Hashemite influence.[33] In the autumn of 1915 Faisal had already found support among Damascene notables and the secret societies active there, and the uprising in the Hijaz was initially planned in concert with a similar movement in Syria headed by members of the Arabist movement al-Fatat. The latter continued to play a useful role as propagandists and Hashemite emissaries once the revolt was launched.[34]

Arabism was also a means of recruiting the core of a regular army from former Ottoman officers. Members of al ‘Ahd, an Arabist secret society that drew its following from Arab officers (in particular Iraqis) in the Ottoman army, were especially prominent in what came to be known as the “National Arab Army.” The Ahd’s acknowledged leader, ‘Aziz ‘Ali al-Masri, was briefly (and also unhappily) Hussein’s chief of staff, and Iraqi officers led the Arab forces that took part in the battles around Ma’an and Tafila in 1918.[35] However, men like Ja‘far al ‘Askari and Nuri al-Sai‘d were the exceptions rather than the rule among the Arabs serving in the Ottoman cause. Only a fraction of Ottoman deserters and a small minority of prisoners of war joined the Arab forces. On the whole, the nationalist officers kept to training and operational tasks in the Hijaz or in the forward base established in Aqaba after 1917.[36] The bulk of the Hashemite army consisted of bedouin irregulars who functioned as guerrillas on Allenby’s “eastern flank” as he advanced into Palestine.

The bedouin irregulars stamped the Arab Movement with a tribal character. This ensured that whatever the motives of its instigators, the form and content of the Arab Revolt reproduced traditional patterns of political change in the rural hinterlands of the Middle East.[37] A protean Arab sentiment, for the most part in the form of ethnic pride in being Arab, was certainly in evidence among the tribespeople.[38] However, the ideas of the Damascene secret societies meant no more to the rank and file of Hussein’s following than they did to the tribespeople of al-Karak. In the Hijaz during World War I, the bedouin, in the words of T. E. Lawrence, “were fighting to get rid of an empire, not to win it.”[39]

The forces of the revolt failed to take Medina, which held out until January 1919, and instead progressed northward toward Damascus by the creation of a “ladder” of tribal allies along the western edge of the Arabian plateau. Guns, grain, and gold, made available by a British subsidy that ran to £125,000 per month, were the means by which the ladder was fashioned.[40] Where material incentives failed, the threat posed by the Hashemite advance was often enough to elicit a tribe’s submission.[41] The two forms of cooperation made for an unstable relationship with the tribes. Some defected once the Hashemite army moved on or once payments ceased. In the areas liberated from the Turks, Hashemite authority was patrimonial. A Council of Ministers was established at Mecca, but actual power was wielded by the staff of the Hashemite princes waging the campaign. Their agents—most often recruited from their own relatives, the eight-hundred-strong network of ashraf—were dispersed among the tribes, where they mediated local disputes and enforced Hussein’s writ in cooperation with local notables according to the norms of tribal practice.

Wartime food shortages and the disruption of food supplies through the blockade of the Hijazi coast and the Indian Army’s control of trade routes into Kuwait held the key to the Hashemite advance. Contemporaries such as Ranzi, the Austrian consul in Damascus, saw clearly that the revolt “was not only the making of the dismissed Amir [Hussein],” but traced its cause to the “the food crisis of the tribes.” The latter was in turn attributed to “woefully insufficient” deliveries of food, particularly grain, from Syria and Palestine. Together with the closure of the sea route, the shortage of grain left the Hijazi tribes “in dire straits and therefore dependent on the goodwill of the English.”[42]

In the first phase of the revolt, therefore, it was British subsidy as much as Sharifian prestige that enforced Hussein’s leadership. Moreover, it was the threat of famine, induced by naval blockade and the disruption of food supplies to the Hijaz, that allowed the sharif to channel local solidarities and rally the bedouin.[43] Otherwise, the Hashemites’ patrimonial methods failed to weld their following into a coherent national movement. Beyond the pecuniary ties forged by British gold, the only ideological element that joined the Hashemites to their local supporters was a common antipathy to Ottoman centralization. Hussein manipulated the bedouins’ interest in autonomy for dynastic ends, and only adopted the rhetoric of Arabism once the fortunes of war opened new vistas for himself and his sons in the Fertile Crescent. The trajectory of the Arab Revolt meant that in the spring of 1917 it was the tribes of Transjordan that held the key to the glittering prospects promised by MacMahon, and the occupation of Wajh by Faisal in February 1917 opened the way for their induction into the revolt.

| • | • | • |

The Course of the Arab Revolt (II): The War in Transjordan, July 1917–September 1918

In southern Syria as in the Hijaz, the outbreak of war and the Allied naval blockade inflicted bitter hardship on the population. The memoirs of ‘Awdah al-Qusus record that the blockade brought shortages of sugar, rice, and kerosene, and that the choking off of imports “raised the price of cloth tenfold.” Matters were exacerbated by Ottoman requisitions. Draconian measures were envisaged that would leave cultivators with a minimal supply of seed and a meagre daily ration of three hundred grams of wheat per person. At the same time, grain, camels, and horses were purchased at unfavorable prices and with a paper currency that devalued rapidly in the face of wartime inflation.[44] An additional burden was imposed by the general mobilization decreed by the Porte, threatening to conscript all men of military age.[45]

A cycle of inclement weather and environmental disaster added to the burdens of war. Until the 1917–18 season, the war years were marked by drought and harvest failure. In 1914, al-Karak and southern Syria suffered an infestation of locusts “that destroyed all fruit trees and crops despite the governments best efforts to combat the plague.”[46] The decline of cereal production was accelerated by the drain of seed, men, and, above all, draft animals to the war effort. Even in the face of soaring food prices, the result was a steady fall in the surplus marketed through official channels and a contraction of the area of grain cultivation.[47] The greed of speculators and misguided attempts by the authorities to corner the grain market brought famine to the towns and coastal provinces of Syria by the winter of 1915–16.[48]

Hunger and the exactions of the Ottoman war regime were the most likely cause of the deep well of Arabist sentiment revealed by T. E. Lawrence’s reconnaissance of the Hawran and Transjordan in May and June 1917.[49] By then, most of the northern bedouin had established links with the Sharifian forces ensconced at Wajh under Faisal, and the Arabist party in Damascus counted such tribal shaykhs as Nuri al-Sha‘alan of the Ruwalla; his son Nawwaf, “the most advanced thinker in the desert”; and Talal al-Fayez and his son Mashhur of the Bani Sakhr as adherents.[50] However, of all the Transjordanian bedouin, it was only a dissident section of the Huwaytat—in effect ‘Awdah abu Tayeh and his Jazi followers—who openly declared support for the revolt in 1917. ‘Awdah, together with individual tribesmen from the Shararat, the Sirhan, and the Ruwalla, was recruited into the Hashemite confederacy between February and July of 1917, and he spearheaded the advance through the Wadi Sirhan, which took Aqaba on the 6th of July 1917.[51]

The occupation of Aqaba provided a base for expansion into southern Syria, and Arab forces under Zayd, the youngest of Hussein’s sons, occupied Wadi Musa and Tafila with the support of local villagers in the autumn of 1917.[52] However, Zayd found himself overextended in trying to take al-Shawbak, where the Hishah forest had become a vital source of lumber for the Hijaz Railway, and Ma’an held out in the face of repeated Arab assaults until the end of the war.[53] North of the Wadi al-Hasa, al-Karak, where “Sami Pasha’s energetic action in 1910 ha[d] not faded from popular memory,” remained firmly in the Ottoman orbit throughout the war.[54]

Two British incursions were mounted across the Jordan with the aim of establishing Faisal in central Transjordan in the spring of 1918. The first “Transjordan raid,” launched in late March, briefly occupied al-Salt, but failed to take Amman. Outfought and out-thought by the Turks, the army was forced to retire across the Jordan on April 2. The second Transjordan raid (April 30–May 4, 1918) was compromised by poor intelligence and the failure of promised support from the Bani Sakhr to materialize. The failure of the two raids dealt a severe blow to British prestige—and consequently to the credibility of the Arab Movement. Moreover, Allenby’s forces were weakened further by the withdrawal of men and material to meet the Ludendorf offensives on the Western Front.[55] As a result, the forces of the revolt made little progress north of the al-Hasa divide until the defeat of the Central Powers, and until Allenby’s victory at Megiddo brought about a general Turkish collapse in the closing stages of the war.

By September 1918, when hostilities in Transjordan ceased, the northern tribes had played a relatively minor role in the revolt. While sections of the Ruwalla were involved in “minor disturbances” in the vicinity of Dera‘a as early as October 1916, the tribe as a whole extended only passive support to the Hashemites before May 1918.[56] Both Nawwaf and Nuri continued to receive Turkish subsidies while enriching themselves from the contraband trade.[57] The latter shifted decisively to the Sharifian side only after his camp at Azraq was bombed by the Turks in June 1918.[58] The Bani Sakhr appear to have hedged. The paramount shaykh of the tribe, Fawwaz al-Fayiz, refused to supply camels for the Turkish attack on the Suez Canal in 1915 and signaled his allegiance to Faisal in January 1917.[59] However, his brother Mithqal recruited three hundred men to the Turkish cause, and Fawwaz himself attempted to deliver Lawrence to the Ottoman authorities in Zizya in June 1917.[60]

By agreement with Jamal Pasha, absolute ruler of Syria during the war, the tribes of al-Karak were exempted from conscription in return for supplying auxiliaries to the Ottoman forces operating in their vicinity. Reinforced by Ottoman cavalry and bedouin from the Bani Sakhr, the Matalqa Huwaytat, and the Ruwalla, al-Karak’s shaykhs raised five hundred horsemen for an attack on the forces of the revolt in July 1917. While the bedouin held back at the crucial moment, the Karakis engaged the Sharifians in a three-hour battle at Kuwayra, looting five hundred sheep in the process.[61] The Turks found it necessary to exile a number of Christian notables from al-Karak (as well as from the related tribes of Madaba) in the latter half of the war.[62] However, the loyalties of the Majali and prominent shaykhs such as Husayn al-Tarawnah remained Ottoman until the fall of Damascus.[63]

In al-Balqa, the ‘Adwan and their tribal followers supported the Turkish cause. The memoirs of Fritz von Papen, then with the Fourth Army, record that the Ottomans “maintained excellent relations with . . . the nearby Arab tribes whose sheikhs often visited Es Salt to make their obeisances.” Al-Balqa’s Christians, however, were consistent sympathizers of the revolt throughout the war. After the first Transjordan raid occupied al-Salt, the town’s Christians (as well as tribal allies and supporters from the faction known as the Harah) chose to evacuate the district alongside the retreating British.[64] By contrast, Transjordan’s Circassian minority under Mirza Pasha Wasfi was active in support of the Turks.[65] Circassians in Wadi al-Sir fired upon British forces during the second Transjordan raid, and a “tribal brawl” broke out between their kinsmen in Suwayleh and Salti Christians during the first Allied incursion.[66]

From the perspective of the Hashemite historians, the stalling of the northward progress of the revolt until the last stages of the war is surprising. No doubt there is some truth to their contention that the Turks played on local differences and went out of their way to conciliate local shaykhs and notables. In Karak the Ottomans fanned a feud between the Christian clan of al-Halasa and the Yusuf section of the Majali. The latter’s shaykh, Rafayfan al-Majali, who had succeeded Qadr as the most influential figure in the district, was made an Ottoman mutasarrif after the Ottoman garrison withdrew in the fall of 1918.[67] Once the Sykes-Picot Agreement was made public by the victorious revolutionaries in Russia, the Turks also played effectively on fears that Allied victory would bring rule by Christian powers and cast doubt on the motives of the Hashemites.[68] Finally the shaykhs of the Bani Sakhr and the ‘Adwan, as well as less significant figures among the Ruwalla, were recipients of Turkish honors and subsidies that kept them from openly siding with the sharif.[69]

Nevertheless, an alternative explanation for the passivity of the tribes is needed, particularly as honor and subsidy were also available from the Sharifian side. The sanction of Ottoman repression must have been of key importance in the first phase of the war in Transjordan. The Turkish hold on Transjordan had been reinforced since 1914 by the presence of the Ottoman Fourth Army, which had its supply center at Jiza some forty kilometers south of Amman. Together with the mobility bestowed by the Hijaz Railway, this allowed the Ottomans to police the Balqa and reinforce their hold on al-Karak and Ma‘an at the first sign of trouble. In the summer and autumn of 1917 both Faisal and Lawrence were reluctant to push on into the Balqa and ‘Ajlun for fear that Turkish retribution would fall on defenseless villages should an uprising prove premature.

The Bani Sakhr, as the second Transjordan raid illustrated, would have been the logical choice to form the next rung of the Hashemite ladder after the capture of ‘Aqaba. However, the concentration of Ottoman forces in the western part of the tribe’s dirah (tribal territory) placed severe constraints on its room to maneuver. While “unassailable” in the steppe east of the Hijaz Railway, the Sukhur faced “retribution . . . once the summer droughts force[d] them back into the pastures west of the railway.” Moreover, their estates at Jiza, Dulaylah, Natl, and elsewhere along the Hijaz Railway added to the tribes’ vulnerability, enabling the Turks, in the words of a British intelligence report, “to put a further turn on the screw” by denying them summer provisions and threatening the incomes of their shaykhs.[70]

The plight of the Bani Sakhr illustrates the fact that, in contrast to the Hijaz, the logistics of food supply in the north Arabian desert (Badiyat al-Sham) worked against the revolt. An Arab Bureau report in the winter of 1917 argued that the various components of the great ‘Anaza tribal confederation that held the key to the revolt’s success in Syria (the Dhana Muslim—Ruwalla, Muhallaf, and Wald ‘Ali on the Shami side of Syrian Desert, and the Amarat to the east) would not join the revolt while the Ottomans controlled the settled areas and, therefore, the markets on which they relied for subsistence. Even the most powerful of the northern bedouin, Nuri al-Sha‘lan of the Ruwalla, would “not fight openly for the Sharif until his tribe of over 70,000 souls is secure, not only of arms, but of food.”[71]

Moreover, the last year of war, when Allenby was well established in Jerusalem and could counterbalance Turkish power, brought ample rain. According to contemporary reports, the bumper harvests that resulted left “the bulk of the rural population in (the) grain producing districts of inland Syria . . . with enough grain in the summer of 1918.”[72] With Ottoman resources stretched by the confrontation with Allenby and the need to supply Ma‘an, it is likely that cultivators in Transjordan were able to evade requisitioning agents and accumulate the grain surpluses documented by Damascene observers in the Jabal Druze. This was almost certainly true of those bedouin landlords who could harvest their crop and then follow their kinsmen into the steppe east of the Hijaz Railway, where the grain could be exchanged for contraband or Sharifian gold.[73] As the grain flowed south to provision the forces of the revolt in Aqaba, Transjordanians could gain access to the guns and gold the revolt traded in without the risk of actually participating.

Once the minorities are excepted, the pattern of participation in the revolt in Transjordan seems to be of scattered initiatives in support of the Sharifian cause north of the Hasa divide, with collective action in its favor being confined to the Huwaytat and the villagers in the environs of Tafila and Wadi Musa. Variations in the power and reach of the Ottoman state and—as was the case in Hijaz—the incidence of food shortage and hunger best explain overt support for the Arab Movement. In the grain-deficient south, where the hold of the Ottoman state was both recent and unsure, the specter of hunger drove sections of the Huwaytat into the arms of Faisal. From al-Karak northward, the presence of the Fourth Army was a deterrent to opportunistic action in favor of the revolt before 1918. By then a good harvest and slackening Ottoman impositions may have left a surplus of grain in the hands of cultivators. Both fallah and bedouin could afford to straddle the fence until Faisal’s victory appeared inevitable.[74]

| • | • | • |

War’s Aftermath: Faisal’s Rule and the Resurgence of the Local Order

Faisal’s reign in Damascus lasted twenty-two months (October 1918–July 1920) and was initiated by his father annexing Ma’an and Aqaba to the Hijaz.[75] From the beginning, his fledgling government faced almost insuperable problems. Allied forces occupied much of Syria as part of three Occupied Enemy Territory Administrations (OETAs). France’s control of OETA North in particular threatened to choke the landlocked interior under Faisal’s control. The economy of Syria was in any case devastated by war. Agricultural production and distribution was severely disrupted, and the towns and coastal areas were close to famine from hoarding, speculation, and graft. The monetary system was in a state of near collapse due to the devaluation of the Turkish lire in the first months of the new regime. The road and railway system had been damaged during the war, and transport was almost at a standstill.[76]

In the midst of the postwar chaos, Anglo-French policy moved fitfully toward implementing the Sykes-Picot Agreement. By 1920 the French interpretation of Sykes-Picot had prevailed, and British forces withdrew from the Syrian interior. Faisal was unable to head off a French occupation of Damascus after the formal division of Syria between the powers at St. Remo in April 1920. Proclaimed king by the Syrian Congress in March 1920, he was forced to abandon his capital four months later as the French army of the Levant under General Gouraud advanced upon it from Beirut. Faisal moved to Haifa and thence to Europe to pursue his cause by diplomatic means. Many of his supporters in the Istiqlal Party fled Damascus for neighboring Arab countries after an engagement with the French at Maysalun. The greater part of these exiles established themselves in Amman, which was rapidly turned into the center of resistance to the French.

Transjordan dissolved into tribal strife as Ottoman rule collapsed. Contemporary accounts speak of the educated and the propertied fleeing the country, while crowds burned the land registries and tax offices in an effort to rid themselves of fiscal obligation or debt.[77] The situation deteriorated further under Faisal. Although local shaykhs and “petty notables” from Ma‘an, ‘Ajlun, and al-Salt took part in Damascene politics, the unified Faisalite administration established in Amman wielded little effective power. The gendarmerie were underpaid and inadequate, and most of Transjordan’s inhabitants refused to pay tax. In al-Salt, the population drove out officials charged with conducting a census and registering the population for conscription.[78] Even before the withdrawal of the British from OETA East in December 1919, bedouin raiding resumed. The Bani Sakhr attacked farms belonging to Salti Christians between Madaba and Amman, and the Balqa tribes began to demand restoration of the land allocated by the Ottomans to the Circassians.[79]

On the eve of the French occupation of Damascus, the instability in Transjordan threatened to spill over into Palestine. The sedentary clans of Bani Kananah—perhaps encouraged by members of the Istiqlal native to the Hawran, including such radical nationalists as Ahmad Muraywid and Ali Khulqi (the latter a native of Irbid)—raided Jewish settlements in Galilee. The raiders engaged British forces at Samakh and suffered a number of casualties as RAF planes strafed them on their way back across the Jordan. Kayed al-Ubaydat, the paramount shaykh of the nahiyah (the lowest level of the Ottoman provincial hierarchy) was among the dead.[80] The Samakh raid seemed to confirm Allenby’s fears that abandonment of OETA East would leave Palestine’s right flank “in the air, threatened by all the Druze and bedouin tribes.”[81] Herbert Samuel, who was high commissioner in Jerusalem and cautiously sympathetic to Zionist pleading, now called for the occupation of Transjordan west of the Hijaz Railway.[82]

Samuel’s advice was at first resisted by Whitehall, which was fearful of the cost of occupying Transjordan. However, the fall of Faisal brought renewed interest in the country. The area lay astride the lines of communication between Mesopotamia and the British base along the Suez Canal, and France’s occupation of Damascus prompted the fear of a further move southward to cut the land corridor with Iraq.[83] Therefore the foreign secretary, Lord Curzon, recommended an “inexpensive solution,” whereby requiring a token presence east of the Jordan would be used to keep the area in the British sphere.[84] In August 1920, a day after Faisal’s departure for Europe, Samuel convened a meeting of shaykhs and notables from al-Karak and al-Balqa at al-Salt and informed them that Transjordan was to be placed under a British mandate. However, the inhabitants were to form their own administrations in each of the Salt, Karak, and ‘Ajlun districts, subject to the advice of British political officers responsible to the high commissioner in Jerusalem.[85]

Regional animosities prevented representatives from ‘Ajlun from attending the meeting with Samuel. Therefore the message was relayed to them by a Major Somerset (later Lord Raglan) at a meeting in Um Qais on September 2.[86] Istiqlalists, including Muraywid and Khulqi, attended the Um Qais meeting, and their presence injected a more radical tone into the proceedings. The assembled shaykhs demanded that Somerset accept a series of nationalistic demands, including the incorporation of parts of the Hauran north of the Yarmouk into the government of ‘Ajlun’s jurisdiction, the unification of the three local governments under a single ruler, a British (as opposed to a French) mandate over Syria, and above all a guarantee that Transjordan would be excluded from Zionist colonization. Somerset was forced to sign a “treaty” incorporating these provisions (the so called Treaty of Um Qais) before proceeding to Irbid.[87]

In any event, the government of ‘Ajlun formed at Irbid proved unable even to rule the qaza (Ottoman district). Friction with the al-Kura soon became apparent, whose paramount shaykh, Klayb al Shraydah, was not represented on the governing council formed in Irbid. Within a week, a separate government of Kura had been established, with Dir Abu Sa‘id as its capital. Following the example of Kura, the dominant clans in four of ‘Ajlun’s nahiyyats (Jabal ‘Ajlun, al-Wustiyya, al-Mi‘radh, and Jarash) established autonomous administrations.[88] The most notable event in ‘Ajlun at the time had a tribal rather than an Arabist coloring. The villagers of Ramtha—then still under titular French control as part of the Hawran—repelled a bedouin raid on the district, inflicting a severe defeat upon the Bani Sakhr.[89]

Farther south, an elected council was established at al-Salt to rule the district alongside the head of government, Mazhar Raslan (a native of Homs who had served as governor of the same district under Faisal). The ‘Adwan were represented on the council, but the Bani Sakhr boycotted its proceedings in favor of a rival government established at Amman by Mithqal al-Fayiz’s Damascene brother-in-law, Sa‘id Khayr. As a result the Balqa also divided along tribal lines.[90] A council similar to Salt’s was established in Karak under Majali leadership. As was the case elsewhere, its procedures remained tribal and it failed to pay its gendarmerie or impose taxation on the district’s tribes. Despite the best efforts of Alec Kirkbride, the British advisor, the grandly named “government of Mo’ab,” lapsed into internecine tribal conflict and an acrimonious rivalry with Tafilah to its south across the Hasa divide.[91]

The pattern throughout Transjordan at the end of Faisal’s rule was of a resurgent local order and a renewal of the tribal particularisms on which it was based. The only effective steps toward stabilizing the country were taken by the British. One of the political officers dispatched by Samuel, Captain Brunton, formed a regular body of cavalry and machine gunners in Amman. The new force had the explicit aim of curbing bedouin raids upon the settled population and was initially recruited from the Circassians settled by the Ottomans for the same purpose.[92] In October 1920 the force successfully collected taxes from Sahab and imposed peace after tribal strife in Madaba.[93] Shortly afterward it was taken over and expanded by Frederick Peake into the new “Reserve Force” which was to be the nucleus of the future Jordanian army.[94] By the time of its formation, however, the arrival of the Amir Abdullah in Ma’an had eclipsed the local governments and set in motion the events that eventually created a separate entity called Transjordan.

| • | • | • |

Conclusion

The years of war and revolt that marked the end of Ottoman rule in southern Syria provide ample support for Charles Tilly’s contention that war places unusual demands on rural actors.[95] In Transjordan, however, as elsewhere along the desert marches of the Ottoman Empire, the nature of the local order was such that the results of war making were more in keeping with the ideas of Ibn Khaldun than with the sociology of state making in the West. In Western Europe, war imposed new burdens on a more or less “captured” peasantry, extending the extractive capacity of the state as well as its fiscal resources and, in the long run, promoting centralization and state building. In southern Syria and the Hijaz, the onset of war diverted men and material to the frontiers or deployed them along extended lines of communication. At the same time, external subsidy, in the form of British guns and gold, gave tribal actors the means to wage war on the state and to weaken and eventually undermine the “infrastructural power” of the imperial center.

Viewed through the lens of war and famine rather than the rival histories of Arabism, material incentives, rather than Sharifian prestige, determined the course of Hussein’s revolt. The Ottoman entry into the war brought naval blockade and the disruption of food imports in Syria and the Hijaz. The exact impact of these shifts in supply varied with the pattern of development in the late Ottoman period, but in grain-deficient regions like the Hijaz and southern Transjordan, tribes such as the Huwaytat were left more exposed than the more self-sufficient tribespeople north of the Mujib line. The looming threat of hunger provided a lever that the Hashemites and their British allies used to co-opt the southern bedouin and construct the northern rungs of a ladder of tribal allies that took Aqaba in July 1917. However, Transjordanians from al-Karak northward, where grain supplies were more secure and the Ottoman presence more forbidding, preferred to straddle the fence until the last months of the war, and it was Allenby’s victory and the Turkish collapse, rather than the forces of the revolt, that carried Faisal into Damascus in 1918.

In Transjordan, as in the Hijaz, guns, gold, and grain, rather than the appeal of Hashemite nationalism, determined the course of the Arab Revolt and its aftermath. Since Transjordanians were largely tribal and for the most part illiterate, their view of the revolt is exceedingly difficult to determine. Nonetheless it may be surmised that the Transjordanians shared the Hijazi bedouins’ ethnic pride and, by 1916 at least, their hostility to the rule of the CUP in Istanbul. National sentiment may be discerned in the actions of individual shaykhs like ‘Awdah abu Tayeh and in the friendly reception T. E. Lawrence received on his reconnaissance of the Hawran in 1917. During the Faisalite period, a broad Arabist current became apparent in Transjordan, not least in the anti-Zionist form that motivated the raiders of Samakh and the participants in the Um Qais meeting. During the war years, however, Arabism remained latent. Tribesmen for the most part evaded or avoided the state and only took up arms when the Ottoman order weakened and there were good prospects for material gain or pecuniary reward.

In form and content, Hussein’s Arab Revolt was essentially a Khaldunian movement. In the words of Albert Hourani, it was “almost the last instance of a recurring process in the history of the region before modern technology transformed the world.”[96] The world of Ibn Khaldun had, however, changed by the time World War I broke out, and local actors—whether tribesmen or Hashemite—could no longer challenge the Ottoman order on their own. To rise against the Porte, the sharif of Mecca needed external—and in the wartime Hijaz, inevitably British—support. As a result, the power of the movement he launched “was not its own but borrowed from a more powerful patron which in the end . . . abandoned it.”[97] Having entered Damascus, his armies could not hold its citadel. In Transjordan this meant that the years of war and revolt brought a transition to localism rather than to Arabism.

Notes

1. For examples, see Madi and Musa, Tarikh sharq al-Urdunn fi al-qarn al-‘ishrin.

2. Musa, “The Rise of Arab Nationalism and the Emergence of Transjordan,” p. 250.

3. Ibid.

4. Tibi, Arab Nationalism: A Critical Inquiry, p. 89; and al-Sayigh, Al-hashimiyyun wa al-thawra al-‘arabiyya al-kubra.

5. Kazziha, The Social History of Southern Syria (TransJordan) in the Nineteenth Century, pp. 28–29.

6. Their continuing importance was highlighted by Jordan’s intemperate reaction (reported in Al-Hayat, 3 June 1996) to remarks by Mustapha Tlas, Syrian defense minister and sometime historian of the Arab Revolt, that questioned Jordan’s “nationalist” origins; and by the imprisonment of the prominent Islamist Layth Shubaylat on charges of insulting the royal family in a speech that drew heavily on al-Sayigh’s opinion of the Hashemites’ role in the revolt (Al-hashimiyyun wa al-thawra al-‘arabiyya al-kubra). See “Fi thikra wa‘ad balfur: muhadharat al-muhandis Layth Shubaylat fi mujammma‘ al-naqabat” (manuscript, ’Irbid, 11 July 1995).

7. Gelvin, “The Social Origins of Popular Nationalism in Syria: Evidence for a New Framework,” p. 645.

8. Gelvin, “Demonstrating Communities in Post-Ottoman Syria,” p. 23.

9. In other words, strengthening what Michael Mann has called the “infrastructural power” of the state—its geostrategic capacity to penetrate civil society and impose effective rule throughout the realm. Mann, “The Autonomous Power of the State: Its Origins, Mechanisms and Results,” pp. 7, 9–11, 29.

10. Zeine, Arab-Turkish Relations and the Emergence of Arab Nationalism, p. 16.

11. Eugene Rogan, “Incorporating the Periphery: The Ottoman Extension of Direct Rule over Southeastern Syria (Transjordan), 1867–1914.” (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1991), p. 11.

12. See Antoun, Arab Village: A Social-Structural Study of a TransJordanian Peasant Community; Andrew Shryock, “History and Historiography among the Balqa Tribes of Jordan” (Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 1993); J. M. Hiatt, “Between Desert and Town: A Case Study of Encapsulation and Sedentarisation among Jordanian Beduin” (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1981); Gubser, Politics and Change in al-Karak, Jordan: A Study of a Small Arab Town and Its District.

13. Rogan, “Incorporating the Periphery,” pp. 11–13.

14. See Peake, A History of Jordan and Its Tribes, pt. 2, passim.

15. Rogan, “Incorporating the Periphery.”

16. Issawi, The Fertile Crescent, 1800–1914: A Documentary Economic History, p. 270. See also Mustafa Hamarneh, “Social and Economic Transformation of TransJordan, 1921–1946” (Ph.D. diss. Georgetown University, 1986).

17. Issawi, Fertile Crescent, p. 313.

18. Rogan, “Bringing the State Back: The Limits of Ottoman Rule in Transjordan, 1840–1910,” pp. 32–57.

19. The exact proportions of land held by the two systems is impossible to determine. Auhagen estimated that only 15 percent of agricultural land remained in fallah hands by 1907, and there is evidence of land hunger in the tightening of the terms of tenancy in the same decade. However, against this must be set Kurd ‘Ali’s view that 95 percent of the land was “suitably distributed” in ‘Ajlun, Balqa, and Karak, and the fact that the only documented reports of land transfers are from well-watered valleys such as the Ghor and the Yarmouk gorge or areas formerly grazed by bedouin in the Balqa. See Issawi, Fertile Crescent, pp. 330–31.

20. Martha Mundy, “Shareholders and the State: Representing the Village in the Late 19th Century Land Registers of the Southern Hauran” (manuscript, Irbid, 1992).

21. Rogan, “Incorporating the Periphery,” pp. 153, 188–90.

22. Ochsenwald, The Hijaz Railway, p. 119.

23. Ochsenwald, “Opposition to Political Centralisation in South Jordan and the Hijaz,” pp. 297–306.

24. Rogan, “Incorporating the Periphery,” pp. 178–88.

25. Ochsenwald, “Ironic Origins: Arab Nationalism in the Hijaz, 1882–1914,” pp. 189–90.

26. See Dawn, From Ottomanism to Arabism: Essays on the Origins of Arab Nationalism.

27. Ochsenwald, “Opposition to Political Centralisation,” pp. 302–3.

28. Dawn, From Ottomanism to Arabism, p. 51.

29. Ibid.; and Kostiner, “The Hashemite Tribal Confederacy,” p. 107.

30. Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East, pp. 79–111, 146–50.

31. Dawn, From Ottomanism, p. 115; Albert Hourani, “The Arab Awakening Forty Years Later,” pp. 209–12. The question of Zionism, and of the morality of Arthur Balfour later undertaking to establish a Jewish national home in Palestine, had not yet arisen. In any case, according to Hourani, “The Hashemites did not oppose it strongly after Britain withdrew its support for [them] in Syria” (211).

32. Mary Wilson, “The Hashemites, the Arab Revolt, and Arab Nationalism,” p. 205.

33. Ibid., p. 214.

34. Tauber, The Arab Movements in World War I, pp. 62–8, 78–9, 122–34.

35. Tauber, Arab Movements, pp. 117–21.

36. Kostiner, “The Hashemite Tribal Confederacy,” p. 136.

37. In the words of Albert Hourani, the course of the Arab Revolt “showed how a new dynasty emerged. . . . An urban family, that of the Hashemite sharifs of Mecca, created around itself a combination of forces, partly by the formation of a small regular army but even more so by making alliances with rural leaders, and it was able to do this by providing both a leadership that could be regarded as standing above the different groups in the alliance, and an aim that could persuade them to rise above their divisions.” Hourani, “Arab Awakening,” p. 206.

38. St. Antony’s College, Private Papers, Arab Bureau, Cairo, Arab Bulletin (henceforth AB), no. 32. This ethnic sentiment long predated the modern Arab Awakening. According to Albert Hourani, “As far back in history as we can see them, Arabs have always been exceptionally conscious of their language and proud of it, and in pre-Islamic Arabia they possessed a kind of ‘racial’ feeling, a sense that, beyond the conflicts of tribes and families, there was a unity which joined together all who spoke Arabic and could claim descent from the tribes of Arabia.” Hourani, “Arab Awakening,” p. 260.

39. Quoted in Kostiner, “Hashemite Tribal Confederacy,” p. 136.

40. Ibid., p. 137.

41. Ibid.

42. Quoted in Schatkowski-Schilcher, “The Famine of 1915–1918 in Greater Syria,” pp. 229–58.

43. It can be seen that the Hijazi tribes initially faced exchange failures that disrupted previous patterns of food distribution and undermined what had become a form of moral economy guiding exchange relations between Ottoman authorities and local producers. As the British blockade disrupted imports, this wartime shift in entitlements took on political coloring. It followed on a decade of CUP policies that threatened the claim on the Ottoman state embodied in surrah payments, while British subsidy allowed for an alternative claim—conditional on participation in the revolt—on the largesse distributed by the sharifs. The net effect was to turn famine and food shortage into a lever that allowed Hussein to mobilize the bedouin to his cause. This use of the term entitlements follows Amartya K. Sen, in Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. Sen argues that the threat of famine stems from shifts in entitlements, or “those means of commanding food that are legitimized by the system in operation in [any] society” (p. 45). Entitlements in Sen’s definition include “the use of production possibilities, trade opportunities, entitlements vis a vis the state,” but explicitly exclude illegal means, such as looting or brigandage, that Arabian tribes habitually resorted to in war or peace. In order to fit Sen’s notion to the anarchic world of the bedouin, it seems necessary to expand the ambit of entitlements by linking them to a wider moral economy. This has been accomplished by Jeremy Swift, “Why Are Rural People Vulnerable to Famine?” pp. 8–15. Swift distinguishes between “exchange failures,” the loss of exchange entitlements or those “bundles” of goods that could be obtained through barter, truck, and trade; “production failures” caused by drought or disease; and the loss of “assets,” which are disaggregated in turn into “investments,” “stores,” and “claims” on kin, patrons, or the state.

44. It seems likely, however, that the inaccessibility of its rural hinterland spared Transjordan the full brunt of these wartime impositions. With the diversion of its coercive resources to the Suez campaign and to the protection of the Hijaz Railway, the internal reach of the Ottoman state was impaired. The embattled provincial authorities had to rely on local proxies or a skeletal apparatus of elderly employees to collect grain. Thus in Karak ‘Awdah al-Qusus and Husayn al-Tarawnah were brought in as partners of the requisitioning agents supplying Medina with local grain; and in ‘Ajlun Saleh al-Tall (a native of Irbid) went about his duties as grain commissioner (ma’mour souq al-hubub) with a meagre escort of four gendarmes. Local sympathies and lack of means of such men must have made sabotage by evasion and concealment an easy matter for local cultivators, and, significantly, al-Qusus’s enterprise ended in failure. See al-Qusus, “Mudhakkarat Awda al-Qusus” (Memoirs of Awda al-Qusus) (manuscript, n.p., n.d.). Al-Tall’s memoirs record resort to “weapons of the weak” such as occurred in the village of Hatem in the Kafarat district, where grain was concealed in a false wall. Saleh Mustafa al-Tall, “Kul Shay’ li al-Taleb Milhim Wahbi al-Tall: Mudhakkarat Saleh Mustafa al-Tall” (Everything for the student Milhim Wahbi al-Tall: Memoirs of Saleh Mustafa al-Tall) (manuscript, Irbid, 1951), p. 40. On weapons of the weak, see Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance.

45. Al-Qusus, “Mudhakkarat Awda al-Qusus,” p. 104.

46. Ibid.

47. Somerset Papers, St. Antony’s Collection, St. Antony’s College, Oxford, Boxes 66 and 84.

48. Schatkowski-Schilcher, “The Famine of 1915–1919.”

49. Jeremy Wilson, Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorised Biography of T. E. Lawrence, pp. 412–15.

50. St. Antony’s College, Private Papers, Boxes 45, 46; Bidwell, Arab Personalities of the Early Twentieth Century, pp. 106, 114–15.

51. Jeremy Wilson, Lawrence of Arabia, pp. 369–75, 416–17.

52. Madi and Musa, Tarikh sharq al-Urdunn, pp. 52–3.

53. St. Antony’s College, Private Papers, Boxes 64, 73, 75.

54. Bidwell, Arab Personalities, p. 154

55. Matthew Hughes, “The Transjordan Raids: Linking Up with the Arabs, March-May 1918” (Ph.D. diss., London, Kings College, 1995), chap. 4.

56. St. Antony’s College, Private Papers, Box 71.

57. Bidwell, Arab Personalities, p. 100; St. Antony’s College, Private Papers, Boxes 92, 97.

58. Jeremy Wilson, Lawrence of Arabia, p. 528.

59. Bidwell, Arab Personalities, p. 101

60. Kazziha, The Social History of Southern Syria, p. 27; and Jeremy Wilson, Lawrence of Arabia, p. 415.

61. Al-Qusus, “Mudhakkarat Awda al-Qusus,” pp. 109–10.

62. Ibid., pp. 113–14; St. Antony’s College, Private Papers, Box 88.

63. Kazziha, Social History, p. 27; Musa, “Rise of Arab Nationalism,” p. 250.

64. Madi and Musa, Tarikh sharq al-Urdunn fi al-qarn al-‘ishrin, pp. 55, 76–77.

65. Kazziha, Social History, p .28.

66. Matthew Hughes, “The Battle of Meggido and the Fall of Damascus: 19 September to 3 December 1918” (manuscript, Department of War Studies, King’s College, London, 1995).

67. Al-Qusus, “Mudhakkarat Awda al-Qusus,” pp. 128–29; St. Antony’s College, Private Papers, Box 88; Madi and Musa, Tarikh sharq al-Urdunn fi al-qarn al-‘ishrin, p. 55.

68. Madi and Musa, Tarikh sharq al-Urdunn fi al-qarn al-‘ishrin, pp. 53–56. Nuri al-Sha‘alan was particularly suspicious of the Sykes-Picot Agreement and British duplicity. At a meeting with T. E. Lawrence in Azraq in the spring of 1917, Nuri seems to have extracted a pledge from Lawrence to submit to retribution and even death if Britain failed the Arabs. Jeremy Wilson, Lawrence of Arabia, pp. 414, 1071.

69. Madi and Musa, Tarikh sharq al-Urdunn fi al-qarn al-‘ishrin, pp. 53–6; al-Qusus, “Mudhakkarat Awda al-Qusus”; St. Antony’s College, Private Papers, AB, no. 88.

70. Bidwell, Arab Personalities, p. 114.

71. St. Antony’s College, Private Papers, Box 71. Similarly it was argued that on the other side of the Syrian Desert the Amarat would not join the revolt “until our frontier on both Euprates and Tigris is far enough northwards to control the Amarat markets.”

72. Schatkowski-Schilcher, “The Famine of 1915–1919.”

73. St. Antony’s College, Private Papers, Box 91.

74. In terms of the framework developed above, the northern tribes seem to have retained enough production entitlements to remain above a subsistence threshold, and were therefore not driven to revolt out of desperation or out of outrage at the violation of the norms of their risk-averse moral economy.

75. Kazziha, Social History, p. 33.

76. Khoury, Urban Notables and Arab Nationalism: The Politics of Damascus, 1860–1920, p. 82; Qasimiyyah, Hukumah al-‘Arabiyyah fi Dimashq, pp. 218–25, 231–33.

77. F. G. Peake Papers, Imperial War Museum, London, “Biographical Fragments.”

78. Kazziha, Social History, pp. 34–5; Musa, “Rise of Arab Nationalism,” p. 252.

79. Kazziha, Social History.

80. Frederick. G. Peake, “Transjordan,” 378.

81. Hughes, “The Transjordan Raids,” p. 233.

82. Wasserstein, The British in Palestine: The Mandatory Government and Arab-Jewish Conflict, 1917–1929, pp. 73–89. The railway itself marked the so-called Meinertzhagen Line that Chaim Weizman wanted as the eastern frontier of Palestine. A. S. Klieman, Foundations of British Policy in the Arab World: The Laird Conference of 1921, pp. 205–8.

83. H. Diab, “Ta’sis Imarat Sharq al-Urdunn,” Shu’un Falastiniyya, no. 50–51 (October-November 1975): 271. Cited in Hani Hourani, Al-tarkib al-iqtisadi al-ijtima‘i li sharq al-Urdunn: muqaddimat al-tatawwur al-mushawwah (The Socio-Economic Structure of Transjordan: A Prologue to Distorted Development).

84. Mary C. Wilson, “King Abdullah of Jordan: A Political Biography” (Ph.D. diss., Oxford University, 1984), pp. 205–7; Diab, “Ta’sis,” p. 271.

85. Eyewitness accounts of the al-Salt meeting report that Samuel tried to tempt the gathering by promising supplies of sugar and rice. Al-Qusus, “Mudhakkarat Awda al-Qusus,” p. 134. However, the assembled notables remained unenthusiastic until Samuel agreed to pardon two fugitives from the Palestine government, ‘Aref al ‘Aref and a youthful Haj Amin al-Hussaini, who had attended under the protection of Rafayfan Majali and Sultan al-‘Adwan. Abu Nowar, The History of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, p. 25.

86. Madi and Musa, Tarikh sharq al-Urdunn fi al-qarn al-‘ishrin, pp. 103–4.

87. Ibid., pp. 104–9.

88. Madi and Musa, Tarikh sharq al-Urdunn fi al-qarn al-‘ishrin, pp. 109–14; Hamarneh, “Social and Economic Transformation of TransJordan,” pp. 109 ff. Jordanian historians hold that these essentially tribal rivalries may have been encouraged by Somerset, who “seemed to excel in the . . . craft of ‘divide et impera.’” Abu Nowar, History of the Hashemite Kingdom, p. 31. See also Hamarneh, “Social and Economic Transformation,” p. 110. Against this must be set Somerset’s own papers, which at times show him working to unify ‘Ajlun with the other districts to the south. Thus a letter to his father dated January 28, 1921, speaks of a meeting in Jerash “a week ago . . . where we had an unsuccessful meeting to try and combine Salt and ‘Ajlun.” St. Antony’s College, Private Papers, Somerset Papers.

89. Musa, “Rise of Arab Nationalism,” p. 253.

90. Madi and Musa, Tarikh sharq al-Urdunn fi al-qarn al-‘ishrin, p. 115.

91. Hamarneh, “Social and Economic Transformation,” pp. 108–9.

92. Dann, Studies in the History of Transjordan, 1920–49: The Making of a State, p. 21.

93. Ibid., pp. 21–25.

94. Jarvis, Arab Command: The Biography of Lieutenant Colonel F. G. Peake Pasha, pp. 69–70.

95. Tilly, As Sociology Meets History, p. 121.

96. Albert Hourani, “The Arab Awakening Forty Years Later,” p. 206.

97. Ibid.

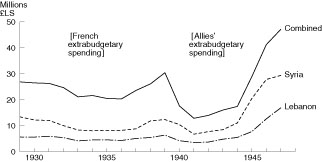

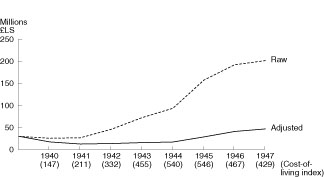

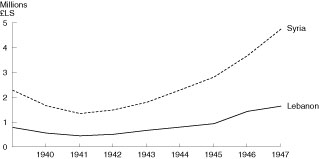

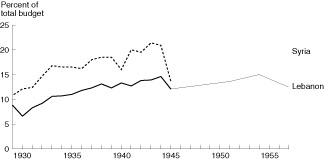

3. The Climax and Crisis of the Colonial Welfare State in Syria and Lebanon during World War II

Elizabeth Thompson

The first and most profound effect of World War II on Syria and Lebanon was fear—fear of famine. “In early September 1939 we were preparing for the new school year when the airwaves carried terror to our souls, pounding us all day with news reports of the Second World War,” recalled a Lebanese schoolteacher. “In the next few days, I saw acute pain rise in the breasts of the generation that had lived through the catastrophe of the First War. . . . Work stopped, and business dwindled as a wave of profound pessimism engulfed the country.”[1] The famine of World War I had killed as many as five hundred thousand Lebanese and Syrians. With blockades and poor harvests, fear of its morbid return reigned for the first three years of World War II, fueling riots, hunger marches, and opposition movements.

Déjà vu struck rulers as well as the ruled. General Georges Catroux, the leader of the Free French forces in the Levant who claimed rule of Syria and Lebanon in 1941, recalled his earlier term of service in these countries after the last war. As in 1918, the French were outnumbered by British troops and competed with them for prestige and power, through the delivery of foodstuffs and aid. In 1941 as in 1920, Catroux faced the task of imposing French rule on a hostile population. And as he did so, he recognized many familiar faces among French sympathizers and the nationalist opposition.

But Syrians and Lebanese confronted war and French rule in a manner radically different from twenty years before. Most salient was the emergence of new mass movements organized by political parties, labor unions, religious groups, and women. These movements aimed most of their demands at the government—for political freedom, decent wages, and full education and health care. While women in World War I typically had suffered alone, portrayed in numerous photographs as lone mothers dying of hunger with their children, women entered World War II armed with charitable, educational, and political organizations that would mount incessant protests claiming not only their right to bread but their political rights and right to national independence. While men in the last war had been drafted into the Ottoman army and sent far from home, in this war they were not mobilized. They too entered the war with highly organized movements that would demand government intervention on behalf of workers, families, and business.

And the French position had radically changed since the last war. In 1918, the French had sought to aggrandize their empire; in 1941, they struggled to reconquer it, to take it back from the Vichy government and fend off encroaching German occupation. In June 1941, Syria and Lebanon were the first major territories outside of Africa that the Free French reclaimed by force, a year after Charles de Gaulle founded the movement in London and a scattering of colonies. The Free French were still weak because of their small numbers, and they had had to rely on overwhelming British support in the Syrian campaign. Moreover, they were still either unknown or suspect in the eyes of most French, and they sought desperately to justify their claim to represent true France. Syria and Lebanon were thus to become Free France’s “city on a hill.” There, Catroux sought to realize the ideals the Gaullist movement claimed were authentically French (and absent in the Vichy regime): republicanism, honor, and a fighting spirit. Free France had little materiel and only “moral capital” with which to recapture the prestige of being a Great Power.[2]