Through the Looking Glasses:

From the Camera Obscura to Video Assist

Jean-Pierre Geuens

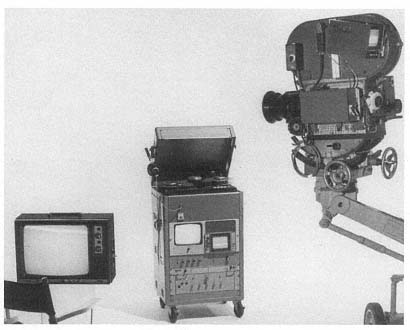

The original video assist apparatus put together by Bruce Hill in 1970

Vol. 49, no. 3 (Spring 1996): 16–26.

The studio is finally quiet. The actors are restless. The crew is ready. "Sound." "Camera." The slate is taken. A voice calls "Action." A voice? Is this really the director, "with his back to the actors,"[1] looking at the scene on a little video monitor? Isn't the director, at least the solid Hollywood professional of old, supposed to sit just next to the camera, facing the action? What's happening here?

Following the trajectory that led from the old-fashioned parallax viewfinders to the contemporary use of video-assist technology, I will argue that "looking through the camera" is never a transparent activity, that each configuration has distinctive features whose design and implementation resonate beyond the actual use of the device. In his still seminal essay "The Question Concerning Technology,"[2] Martin Heidegger warned us that "technology is no mere means,"[3] that the adoption of a new method of production often expresses more than the simple substitution of one tool by another. In Andrew Feenberg's words, "modern technology is no more neutral than medieval cathedrals or the Great Wall of China; it embodies the values of a particular civilization. . . ."[4] Herbert Marcuse is even more radical. For him, "specific purposes and interests of domination are not foisted upon technology 'subsequently' and from the outside; they enter the very construction of the technical apparatus. Technology is always a historical social project: in it is projected what a society and its ruling interests intend to do with men and things."[5] Thus, as far as the camera is concerned, the very appearance of a novel gizmo could itself be significant of cultural or economic changes that have taken place in the film industry prior to the use of the new technology and, in turn, the actual practice of the supplemental device may help shape a different kind of cinema.

In the first years of cinema, getting access to the image that was to be recorded on film was no easy matter. The early cameras could never provide such necessary information. Indeed, not only the pioneer cameras of the 1890s and the

1900s but also the first truly professional cameras used by Holly-wood—the Bell and Howell 2709 and the Mitchell Standard Model—had to resort to peeping holes, miscellaneous finders, magnifying tubes, swinging lens systems, and rack-over camera bodies to give any information at all about the image produced by the lens.[6] At best, the operators were allowed to survey the scene before or after actually shooting it. Crucially missing from their arsenal was the capability to check on exact framing, focusing, lighting, depth of field, and perspective while filming. Although a lens could be precisely focused on an actor's position ahead of time, what happened during the shot, especially if there was any movement, remained a mystery. The operators, in effect, were shooting blind. As they watched through the parallax viewfinder on the side of the camera, a device that produced but a pallid, lifeless, uninviting substitute for the real thing peeked at seconds earlier, they remained outsiders to what was truly going on inside the apparatus. In a way, the mystery of what happened inside the camera during the shooting acted as a synecdoche for the further magic that would be worked on the film in the lab, where it was to be chemically treated and its content at last exposed to view. Only at the screening of the dailies could one know for sure whether the scene was good or needed to be reshot. Such a daunting situtation therefore required steady professional types and, indeed, this is how the "operative cameramen" were described by their peers in the American Society of Cinematographers: "They must be ever on the watch that no unexpected or unplanned action by the players or background changes from the originally planned movement and lighting on the set, occur during shooting. They sit behind the camera, like the engineer at his throttle, ever watching for danger signals."[7] These brave men behind the camera, despite their vigilance, thus stood in a hermeneutic relation to their instrument. The otherness of the machine remained unassailed, its viewing apparatus a numinous, hermetic object standing as a third party between the operator and the world. The best one could do was stand next to the thing, maybe controlling its mishaps or its surges, but, throughout, acknowledging the actual film process as a thorough enigma.

The situation changed in 1936, when the Arnold and Richter Company of Germany introduced continuous reflex viewing with its new Arriflex 35mm camera. The solution was truly elegant: by mirroring the side of the shutter that was facing the lens and tilting it at a 45-degree angle, the light that was not used by the film when the latter was intermittently moving inside the camera was now made available to the operator for viewing purposes. Suddenly, the deficiencies that had marred the early camera systems were eliminated as operators, looking through the lens during the filming, gained maximum control over the images they were shooting. In fact, the smoothness of the Arriflex

solution hid a paradox. Even though the operator may believe he or she sees what the film gets, technically speaking one never actually witnesses the same instant of time that is recorded on film because of the fluctuating movement of the shutter—when the operator gets the light, the film does not, and vice versa. More importantly, this means that the access to the lens is punctuated by the blinking presence/absence of the mirrored shutter. In my view, this flickering implies more than a simple technical chink; it radically transforms the linkage between the operator, the camera, and the world by literally embodying the eye within the technology of the apparatus itself.

Indeed, if we go back to the early years of still photography for a moment, there was always a sense of awe when the operator's head finally disappeared under a large black cloth in order to take the picture. "What do you have there: a girlfriend?" a model asked of Michael Powell's protagonist in Peeping Tom (1960), a comment that clearly exposes the prurience of the act. In a similar fashion, on the motion picture set, the view through the reflex viewfinder quickly became fetishized, the actual practice exceeding the useful aspect of checking on the parameters of the scene. Crew hierarchy determined who got to take a peek. Yet the static image one could witness when the camera was at rest had finally little to do with what happened during the real shooting, when the operator alone received the full force of the system. Then the impact was truly stirring; due to the saccadic nature of the shutter's rotation, the effect on the eye was nothing less than phantasmagoric. Because the other eye of the operator remained closed during the filming, the flickering light on the ground glass became thoroughly hypnotic, even addictive.[8] For the time of the shot, with only one eye opened onto the phantastic spectacle on the little screen, the operator was very much lost in another world, a demimonde, a netherworld not unlike a dream screen for the wakened.

It is not so much that the frame provides for the operator a "synoptic center of the film's experience of the world it sees," as Vivian Sobchack has suggested,[9] but that what is being seen and the way it is seen combine in bringing forth a unique experience for the person at the camera. Let us consider for a moment the ramifications of what is actually taking place. A scene is rehearsed, then shot a number of times until the director declares him/herself satisfied. Through it all, the same general actions are performed with little change by the actors (basic gestures are duplicated, more or less the same lines enunciated) and the crew moves in sync with the action—a swinging of the boom that keeps abreast of an actor; a short dolly movement that accompanies an action; a dimming of the light level at the proper moment by an electrician; a change of focus by the camera assistant; and, for the operator, maybe a pan or other small readjustment that keeps the scene within the frame. What we have here, then, is no less than a ritual, a ceremony of sorts that also involves repetition, reenactment, and

specific gestures carried out by "practitioners specially trained."[10] On a macro scale, the effect of a ritual is to bond a group, to create a sense of communitas when all participants find themselves sharing an experience. And, characteristically, this is a well-known effect experienced by all in a film crew as the constant repetition of specific actions, performed with only minimal variations, gives each member the sense both of cultic participation in a grand project and of sharing in a larger, collective identity. For the operator who most intimately experiences it all as an eye mesmerized by the spectacle on the little screen, the effect is even more hallucinatory. The sense of time is altered; there is no past or future any more, only a flux, a duration, an endless synchronic moment with actions many times repeated, an epiphany punctuated only by "eternal poses," to use Gilles Deleuze's descriptive words.[11] Because it stands outside mechanical time and physical space, the experience recalls the "oceanic" early moments of life. During that moment, the operator, neither here nor there, stands liminally between two worlds. As he or she merges, to some extent, with the phantom action on the little screen, a communion takes place that integrates the self within an ideal reality. Not surprisingly a certain Ekstase can be reached. The effect then is not unlike that of a trance in a ritual, an experience that also momentarily transforms the individual. No wonder that, after the shot, different members of the crew turn toward the operator and ask: "How was it?"

Others have been sensitive to the reflex feature of the camera for distinct reasons as well. For instance, independent film-makers functioning simultaneously as directors and operators have worked both in fiction and in documentary. Among others, Nina Menkes, Ulrike Ottinger, and Werner Schroeter have always insisted on controlling the camera. In their kind of moviemaking, it makes a lot of sense not just to be present but also to participate in the moment of creation and help deliver the scene through the camera. For Direct Cinema practitioners, however (Richard Leacock, D. A. Pennebaker, and Albert Maysles in the heyday of the movement), the situation is somewhat different. As the subject here belongs not to fiction but to the real world, and the situation, by choice, cannot be rehearsed, there is no question of experiencing a ritual. Instead, the film-maker and the camera seem to merge into one persona that absorbs the scene and responds to it. For the Drew team, for instance, not only is the scene "unscripted, it's unrehearsed . . . for the first time the camera is a man. It sees, it hears, it moves like a man."[12] In other words, through its heartbeat, the pulse of its shutter, the camera now breathes as a human being. And the film-maker, operating like the expert craftsperson of old, carves up the world for the benefit of the viewer, dereifying the structures of daily life, eventually revealing what was either unseen or just obscure moments before. In this case, therefore, the look through the camera functions very much as an example of what Heidegger refers

to as techne , the Greek practice of the craftsperson which brings forth poesis through the work. For Heidegger, the decisive factor is not the tool itself but the "unconcealment" of the world that results from its use.[13]

However, because the rigid division of labor in the Hollywood cinema forbids it, the typical director is almost never the person behind the camera (often sitting, instead, just underneath it). For him or her, therefore, nothing really changed in the substitution of the original apparatus by the reflex camera. The director remains exterior to the camera's process. After orchestrating everybody else's actions, the director gauges the results of the take instantly, in vivo , by gut instinct. Precisely because such directors do not look through a viewing screen during the filming, they literally function as metteurs-en-scène: their scene indeed is the stage, the space where fellow beings move about. What they must be sensitive to is the human intercourse at hand, the social space between people, the presence of objects as well as the flesh of the individuals. All the senses of a director are imbricated in this evaluation. Although the scene is shot in pieces and staged to be captured in a certain way on film, the dramatic action has a reality of its own. It is thus experienced by the director as (to borrow another notion from Heidegger) Zuhandenheit , the ready-at-hand, an involvement with the world through technique that actually supersedes the use of the equipment.[14] Expressly because the director is not looking through the camera, the technology associated with directing remains somewhat in the background, only a subordinate accessory. For Heidegger, what is experienced in this fashion is ontologically quite different from what could be observed through Vorhandenheit , the present-at-hand, the contemplation of a decontextualized subject matter. Directors functioning in the traditional mode thus depend mostly on human rather than exclusively cinematic skills: this does not feel right, that timing is a little off, this character would not really do that.

Furthermore, if we listen to Emmanuel Levinas for a moment, when a face-to-face encounter among human beings takes place, the contact involves more than a mere recording of an action by the eyes.[15] It embodies the most fundamental mode of being-in-the-world. A face, for Levinas, expresses the vulnerability of the being; it is an appeal, a call. The face solicits a human contact beyond cold rationality or calculative thinking. Its sheer presence impinges on the other person's autocratic tendencies. In this light, the director's "vision" of the scene becomes compounded by his/her own presence among the actors. Sharing a unique moment of time, the director becomes thoroughly wedded to the players as fellow human beings who carry their load of pain or distress. Can the director in these conditions (to recall well-known cases in our cinema) remain unaware of the wooden leg of one actor even if it remains off-camera? Can the director not respond to the cancer that is eating up this other actor? Even if we abandon these dramatic examples, is it really possible for the director to leave entirely behind the

lunch shared with some actor, the conversations that went on, the hopes that were disclosed or the fears that were expressed? To go back to Heidegger, the director here does more than take a look (Sicht ) at the scene professionally; emotion is involved as well (Ruchsicht ), a look that involves sympathy, concern, and responsibility. Furthermore, the sharing of a human space and the mutual recognition that takes place between people automatically involve moral claims. One individual temporarily gives something of him/herself to another. Trust matters deeply. Ethics are involved. As a result, the director functions both as a participant in a shared exchange and as a shaman who guides others through a difficult process of shedding off. For such a director, the scene clearly takes place in front of his or her eyes, not behind where the camera is. After the take, the information that originates from the crew is certainly important, but it is purely technical in nature: did the action remain in focus, was the pan smooth, did the mike get in the shot, was the jolt to the dolly noticeable?

A radical departure to this long-standing mode of directing came about as a result of Jerry Lewis's introduction of video as a guide for the director to evaluate the quality of a take. There were of course good reasons for Lewis to do so: this was a logical solution to the problem of the actor/director, who was otherwise unable to check his performance. Buster Keaton would surely have been an ardent practitioner of the new technology. What Lewis did was elegant in its simplicity: he positioned a video camera as close as possible to the film camera, allowing him to view what he had just shot on playback. Although the technology was primitive and the equipment, at the time, heavy and cumbersome, Lewis persevered, and others eventually picked up on the idea. As early as 1968, some motion picture cameras that incorporated plumbicon tubes in the viewfinder (thus splitting the light that normally would go to the operator alone), were used to film a tennis championship in Australia.[16] The next year, videotape playback was used in the film Oliver! (Carol Reed, 1968) to check on the lip sync or the movement of performers. If the tape showed the actor or dancer to be in sync after all, it saved the retake of a difficult and expensive dance number.[17] By most accounts, though, credit for the integration of the video "camera" within the motion picture camera by means of a pellicle (a thin, partial mirror that split the light coming to the operator) goes to Bruce Hill, an engineer/tinkerer who had worked at Fairchild and Mitchell.[18] By 1970, working independently, Hill had modified a Mitchell BNCR and used a one-inch-videotape recording and playback system by Ampex. The subsequent image could be observed on a 17-inch monitor. A variation of this package was used for the helicopter sequences of The Towering Inferno (John Guillermin and Irwin Allen, 1974), the first time such a device was used by the Hollywood establishment.

Not surprisingly, directors shooting commercials were the first to embrace the new technique, for in their work in particular it is very important to check on the exact placement of a product in relation to many other coordinates. With the help of video, minute details could be discussed between representatives of the advertising agency and the technicians. Today, practically all commercial productions use video assist and playback on the set. In contrast, feature directors were distinctly slower in adopting the new apparatus: only 20 percent or so of the productions in the early 1980s used video assist. And although today most do, no more than 40 percent of the shoots bother with a playback system.[19]

On the surface, the use of video assist on the set provided only positive benefits for the director and the crew. For directors, being able to see the picture of the scene being rehearsed meant gaining back some of the control that historically had been lost to operators. For a crew, the advantages could be measured in terms of efficiency. During a shoot, questions keep flying to the operator: is the boom in the shot, where is the frame line, do I need to prop that area, are these people in the shot, how high do I need to light that wall, etc.? A lot of production time is lost as the operator attempts to make clear the parameters of the shot to the gaffer, the assistant director, the boom person, or the prop master. Once video assist becomes available and a large monitor is provided for the various crew members, all they have to do is look at it to answer their own question. In a similar fashion, the light split itself can be subdivided so as to provide a mini-image to the operator's assistant or the dolly grip. It might be more practical indeed for these technicians to look at an image on a monitor than to the scene itself to decide exactly when to initiate a rack focus or a dolly movement. All of these advantages end up saving time, and thus money, for the production.

There were, however, some technical mishaps that initially limited the appeal of the novel apparatus. The early grievances were mostly concerned with the disappearance of the director, who might be locked in a trailer loaded with equipment and who would communicate with the crew and actors only through a loudspeaker. Helen Hayes, for instance, was heard complaining about such a "disembodied voice" when working on Raid on Entebbe (Marvin Chomsky, 1977). And Garrett Brown grumbled that, when he was shooting the maze scene in The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980), "Stanley mostly remained seated at the video screen, and we sent a wireless image from my camera out to an antenna on a ladder and thence to the recorder,"[20] in effect forcing Brown to go back and forth between the maze and the trailer, quite a distance away, just to find out if the take was good. That problem was eventually worked out when directors were able to use the monitor on the set itself. Another difficulty involved the operator: as the video system taps the light

that would normally go to the eye of the camera person, a loss of clarity can be experienced by the operator, in effect making the job more difficult. One reason black-and-white taps have been traditionally preferred over color models is that the former could function with much less light intake compared to the latter. A new color tap though, the CEI Color IV, is said to be almost as economical as the black-and-white models and is thus gaining in popularity. Flickering was another "annoyance" that marred some of the viewing. But there are now new models, such as those factory-installed by Arriflex on its new 535 camera, which incorporate a totally flicker-free tap. Although more traditional directors of photography, such as Haskell Wexler, have indicated their preference for a video image that reproduces the flicker of the motion picture camera, most directors of photography shooting commercials go for the enhanced version, perhaps to soothe the apprehension of clients or agency people who might wonder about the misfiring on the monitor.[21] A fourth difficulty concerned the matching of the image received on the monitor to specific aspect ratios when shooting wide-screen or when using an anamorphic lens. Here the solutions could be makeshift in nature (paper tape can be applied directly on the monitor so as to delimit the 1.85:1 aspect ratio), or electronic (monitors can now switch easily from a squeezed to an unsqueezed image). Finally, using videotape playback after each take may slow down the impetus of the crew because it interrupts everyone's activity—a situation that has limited the use of that particular technique. It might indeed be cheaper to redo a shot immediately than to break the momentum of the cast and crew. For this reason, videotape playback, when used at all, is looked at only after several takes have been shot so as to minimize the disruption.

Moving now from a technical to a cultural evaluation of video assist, we focus on its similarities to the camera obscura, a tool used by many painters in the seventeenth century to replace or supplement their own human viewpoint. Significantly, in both machines, the observer (the painter or the director) no longer confronts the world directly but looks instead at an image formed through an optical contraption. In other words, a mediation is taking place. If the technology remains transparent to its user, he or she, in the words of Svetlana Alpers, "is seen attending not to the world and its replication in [an] image, but to . . . the quirks of [a] device."[22] In his analysis of Vermeer's work, Daniel A. Fink has pointed to a number of optical phenomena directly related to the use of a camera obscura.[23] They are all consequential for the image being produced. For example, whereas in daily life the eye continually refocuses as it engages objects located at different distances, the camera obscura equipped with a lens forces the operator to view the scene through a single plane of focus, in effect making some objects sharper than others. Likewise,

Margo, with Burgess Meredith, looking through the camera

(Winterset , 1936)

whereas Vermeer's contemporaries represented relatively large and sharp mirror images of objects, very much like the eyes would see them, Vermeer's own mirror reflections are comparatively small and slightly out of focus, as they would appear through a lens focused on a different plane. All in all, Fink points out ten such "distortions" introduced by the instrument used by Vermeer.

In the same manner, today, the limitations of video keep interfering with the work of directors of photography because of the differences between what is seen on the monitor and what will be in fact recorded on film. The main culprit here is the lack of resolution of the video image and the fact that its contrast ratio does not match that of the film stock. Shadow detail, for instance, does not show up on the monitor, a situation that inevitably creates doubt about the handling of the lighting scheme. For the same reason, directors have been known to complain when low light levels may simply make it too dark for them to see the expressions of the players on the monitor. And, when using color, everyone frets about the differences between the colors on the set, those on the monitor, and those that will show up on film. In addition, directors of photography have noted that the usual size of the monitor (typically a 9-inch set) used by the director may also make it less likely that action will take place in the background in a long shot or even on the sides of the frame, as the miniaturized or peripheral action would not play well on such small screens.

The action therefore often ends up enlarged and more centered. Beyond this, if the movie is going to be cut digitally, it makes little sense for the production to pay for regular film dailies. As a result, the director will not be aware of the large-screen effect of the film until it is prepared for release in the theaters: a definite drawback. Lastly, the fact that the scene is observed through video technology as opposed to film may have consequences of its own. Film images' fascinatingly rich appearance originates in the random distribution of the silver molecules on the film surface. Each individual frame in effect configures the subject slightly differently. When played back, the scene is reconstructed twenty-four times per second, bringing forth more "livingness" to the eye of the spectator than any single frame could provide on its own. In contrast to this, as Vivian Sobchack describes it, "electronic technology atomizes and abstractly schematizes the analogic quality of the photographic and cinematic into discrete pixels and bits of information that are then transmitted serially . . .,"[24] a design responsible for the "sameness" of the electronic image. In other words, a picture so constituted may not prompt the kind of investment associated with the older technology. And this in turn may produce a viewing situation for the director that demands quick renewal and change, shorter scenes, a point of view that Charles Eidsvik has described as "glance esthetics" in lieu of the older, more traditional "gaze esthetics."[25]

Looked at another way, employee relations on the set have also gone through a subtle restructuring. The operator is no longer the sole source of vision. Someone is now watching over the very guardian of the sight. The situation is not unlike a contemporary version of Taylorism, where work is carefully meted out into distinct components that can be precisely measured through scientific management techniques. Early in the century, for example, Frank Gilbreth, a disciple of Frederick Taylor, determined through the use of photographs a bricklayer's ideal working position. He then attempted to enforce this position on other bricklayers, thus hoping to eliminate minor but wasteful divergences from the more effective stand.[26] However, as work is rationalized and systematized, a subtle de-skilling of the worker's craft occurs. In fact, it is no longer trusted at face value, it is verified through technology until it matches very precisely the demands of management. Andrew Feenberg put it this way: whereas earlier "the craftsman possessed the knowledge required for his work as subjective capacity . . . mechanization transforms this knowledge into an objective power owned by another."[27] On the set then, the camera operator ceases to function as an independent agent who is counted on to execute a difficult move. He/she becomes merely the mechanical arm of the director. The operator, having lost some of the creativity associated with his/her own work, is thus transformed into a semiautomaton. The change eliminates the trust in someone's craft. It reinforces the industrial aspect of film-making, the manufacturing

of a marketable commodity where the picture represents the surplus value of the labor performed by the operator.

Another characteristic shared by the camera obscura and video assist is the apparent objectivity and finality of the image they provide. Because the scene was captured by an optical device, the camera obscura's picture was thought to be necessarily truer to the model than that obtained through traditional human effort. In a similar fashion, the contemporary film director imagines gaining access to the truth of the scene when he or she abandons the actors and watches the take, no longer face-to-face from underneath the camera but indirectly on the monitor. After all, isn't this image the very picture that is being simultaneously recorded on film, the one that will be seen later by the viewers? As Jonathan Crary puts it, in each situation "the observer . . . is there as a disembodied witness to a mechanical and transcendental re-presentation of the objectivity of the world."[28] As a result, the camera obscura and video assist can be said to incorporate within their machinery the Cartesian ideal of the partition between pure body sensations and the mind, with the latter, the true self, inspecting the observations gleaned by the senses. Paul Ricoeur best described this mode of thinking when he called it "a vision of the world in which the whole of objectivity is spread out like a spectacle on which the cogito casts its sovereign gaze."[29] What is at stake here is the authority of an ideal observer, removed from the scene, someone who is no longer operating as a body-in-the-world sharing a space/time continuum with the actors. The latter, instead, are objectified, appropriated for the director's use. As it plucks the scene out of that common, human context, video assist fragments the total experience specific to the traditional directing mode. What takes place in fact duplicates the calculative thinking of the traditional scientific experiment that first sets measurable goals for itself, then authenticates their presence in an ensuing test, thus "guaranteeing the certainty and the exactness"[30] of the project as a whole. Similarly, the contemporary director ends up verifying on the monitor what he/she expects to find there in the first place. The attention, in other words, is on what Heidegger called Vorhandenheit , the foregrounding of technology, of the actual, of what has been worked out during the rehearsals, at the expense of the film still as a project (his notion of Zuhandenheit ), a potential, something not quite yet there, something that remains a becoming, that is still in flux. The present-at-hand, what is already there, takes precedence over what is still outstanding, what could still be created. A metaphysics of presence-through-the-image in effect dominates the day.

What I am suggesting here is that getting access to the image is not an automatic panacea for the director. To illustrate this point, let us look at two films produced and directed by Francis Ford Coppola. On the one hand,

Conrad Hall behind the camera

(Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here , 1969)

Apocalypse Now (1971) emerged from complete chaos and three years of shooting—perhaps the ultimate example of "how not to make a film"—a masterpiece. On the other hand, One from the Heart (1981) was conceived most rationally with the help of the latest electronic wizardry available at the time. From the very beginning of the production, an audiotape of the actors' read-through of the script was combined with storyboard images and temporary music to help the pre-visualization of the film as a whole. Polaroids of the actors' early rehearsals then replaced the drawings, followed by videotapes of the scenes shot on location in Las Vegas. As a result, long before a single foot of film was actually shot, "the whole movie could be seen at any time,"[31] by anyone involved in the film. Furthermore, when the film was ultimately shot in a Hollywood studio, Coppola could watch each take with music and sound effects. And he "was able, at the beginning of each production day, to view an edited version of the previous day's shooting, complete with music and sound effects."[32] The idea was to be able to handle immediately any kink in a scene, any difficulty with the pacing within or between scenes. As each segment of the project could be looked at, analyzed, dissected, film-making in effect became a totally rational enterprise, with the director-engineer at the helm calculating, quantifying, mastering the impact of each and every effect. This total involvement with the ever-present image, the absolute elimination of the mystery of shooting, should have produced the most successful film ever. What Coppola forgot though, in his all-out effort at demagicizing the film process,

James Cameron looking at the video assist

(True Lies , 1994)

is that, paraphrasing Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the director's "vision is not a view upon the 'outside,' a merely physical-optical relation with the world."[33] No more than a poem can be said to exist in the words per se, a film does not reside solely in an image that can be observed on a little screen. During the shooting, it remains instead a becoming, an opening, a possibility that may or may not be realized later on. A film, in other words (still paraphrasing Merleau-Ponty), is as much in the "intervals" between images as it is in the pictures themselves.[34] Fleeing the mystery of creation, the challenges and the claims involved in a face-to-face transaction, the contemporary director thus functions as a distant subject who masters and objectifies others through the supremacy of technique. The lingering of the body in time and space has been replaced by what Nietzsche called an Apollonian frenzy with the eye.[35] The mise-en-scène has turned into mere mise-en-image, a soulless play of isolated, context-free commodities.

Technology must never be accepted at face value. It is not because the science is there that the invention or the use of a machine will automatically follow suit. And not all novel techniques are successfully adopted by the practitioners in the field. One cannot, David F. Noble reminds us, ever simply state that the best existing technology is automatically being used at all times. Instead, we must always replace that assumption with more probing questions: "The best

technology? Best for whom? Best for what? Best according to what criteria, what visions, according to whose criteria, whose visions?"[36] Hence, insofar as video assist is concerned, what are the historical conditions that made its use so widespread? When Jerry Lewis used it there was little interest on the part of other directors to emulate him. Yet, not so many years afterward, in remarkable unison, most American directors ended up adopting his method. What happened in between that brought about this radical change? The answer lies in what Charles Eidsvik has called "the film's industry's defensive maneuvers of the 1970s and the 1980s,"[37] when, to repel the thrust of both television as a competing source of entertainment and videotape as a contending recording medium, changes were made in the kind of cinema that was produced. The writing in effect pushed the plots "into areas in which video could not compete well. . . ."[38] Practically speaking, this meant that the small movies, the psychological films, the non-action pictures, were abandoned to television. Conversely, the theatrical experience was redefined as the larger-than-life action spectacle. Although Eidsvik identifies location film-making as the main beneficiary of these changes, location per se did not prove itself enough of a draw to sell the real movie in the theater over the TV movie of the week. More was needed, and camera pyrotechnics were quickly enlisted to divert and bedazzle the spectator's eyes. These technological advances, however, also eroded the traditional control of the director on the set. First, the very mobility of the Steadicam created a dilemma for the director.[39] What was he or she supposed to do: run after the Steadicam operator or remain ineffectually behind? Second, the Louma crane isolated the camera at the extreme end of its reach, all the time maneuvered from afar by an operator working at a console. Third, cable contraptions of one type or another followed, flying the camera far above the scene. Fourth, helicopters equipped with gyrostabilized systems further extended the reach of the apparatus. Finally, the ease of digital technology pushed film-making toward ever more complex and demanding composite images. All in all, as the "scene" became less and less accessible, directors had no choice but to look at a remote image on a video monitor.

"In choosing our technology," Feenberg suggests, "we become what we are, which in turn shapes our future choices."[40] And so it is that a scene that required an improbable camera position would also benefit from graphic action and various kinds of pyrotechnics, traditional or otherwise—all situations that incidentally also showed up best on the monitors. In other words, whereas it is unlikely that the cinema of Ingmar Bergman would have significantly benefited from the use of video assist, that of Jim Cameron or Robert Zemeckis makes little sense without it. In this type of film-making, in fact, the device itself is no more than an advanced representative of other, more intensive technologies that will later on

enhance the surface appeal of the film in postproduction: digital-image processing, digital editing, digital sound enhancing, etc. And in turn this superior technology, this dazzling maneuverability, this extraordinary display of breathtaking technique is widely advertised, thus staking new claims for the global hegemony of Hollywood. The fire power of the contemporary American film may be less physically destructive than that of the old gunboat, but it nevertheless forces its superiority on the technologically backward national cinemas of Europe, Asia, and elsewhere, threatening their very survival.

For the new American director, however, success speaks for itself and money speaks best of all. Hence, no rejection of the power of technology should be expected. Needed or not, video assist is here to stay, not because it is necessarily the best tool for the job, but because, more than ever, we implicitly trust a machine more than ourselves to tell us about the world. As the objectification of the world through the domination of technique is pushed one notch further, the cogito of old can be said to have been given a more contemporary twist: video, ergo est .